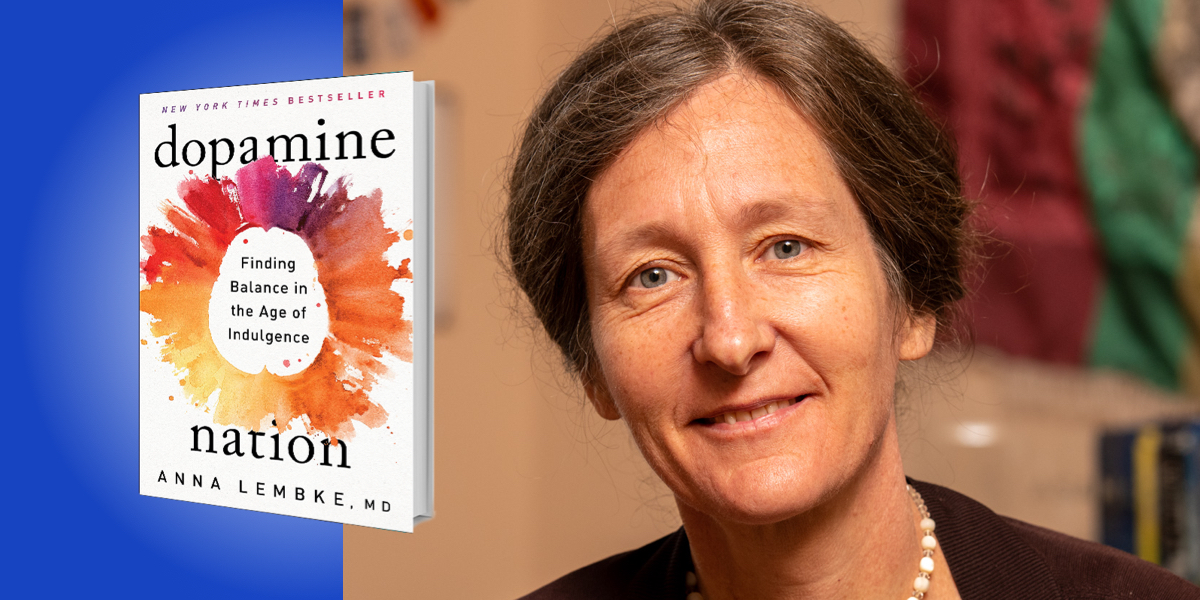

Anna Lembke is the medical director of Stanford Addiction Medicine, program director for the Stanford Addiction Medicine Fellowship, and chief of the Stanford Addiction Medicine Dual Diagnosis Clinic. She is the recipient of numerous awards for outstanding research in mental illness, for excellence in teaching, and for clinical innovation in treatment.

Below, Anna shares 5 key insights from her new book, Dopamine Nation: Finding Balance in the Age of Indulgence. Listen to the audio version—read by Anna herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. The pleasure–pain balance.

One of the most important discoveries in neuroscience in the past 100 years is that pleasure and pain are co-located. The same parts of the brain that process pleasure also process pain. And pleasure and pain work like a balance. When we feel pleasure, the balance tips one way; when we feel pain, it tips the other. One of the overarching rules governing this balance is that it wants to stay level. After any deviation from neutrality, our brains will work very hard to restore a level balance, or what neuroscientists call homeostasis.

For example, I like to watch YouTube videos of American Idol. And when I watch, my brain releases a little bit of the neurotransmitter dopamine in my brain’s reward pathway, and my balance tips slightly to the side of pleasure. But no sooner has that happened than my brain adapts to the increased dopamine by down-regulating my dopamine receptors and dopamine transmission.

I like to imagine this as little gremlins hopping on the pain side of my balance to bring it level again. Not very scientific, I know—but here’s the thing about those gremlins. They like it on the balance, so they don’t hop off once it’s level; they stay on until it has tipped an equal and opposite amount to the side of pain. This is the aftereffect, the hangover, the comedown—or in my case, that moment of wanting to watch just one more video.

“After any deviation from neutrality, our brains will work very hard to restore a level balance, or what neuroscientists call homeostasis.”

If I wait long enough, the gremlins hop off the balance, neutrality is restored, and that feeling passes. But what if I don’t wait? What if, instead, I watch another video and another and another? Pretty soon, I’m no longer watching American Idol YouTube videos. I’m watching YouTube videos of people watching YouTube videos, alternating with memes of Dr. Pimple Popper.

Now, if I keep doing this, I end up with enough gremlins on the pain side of my balance to fill a whole room. They’re camped out for the long haul—tents and barbecues in tow. Once that happens, I’ve changed my joy set point. I need to keep watching YouTube videos—not to feel pleasure, but just to feel normal. And as soon as I stop watching, I experience the universal symptoms of withdrawal from any addictive substance—anxiety, irritability, insomnia, dysphoria, and mental preoccupation with using, otherwise known as craving. This is the hallmark of the addicted brain.

2. Dopamine overload.

This fine-tuned pleasure–pain balance of ours has evolved over millions of years to help us approach pleasure and avoid pain. It’s what has kept us alive in a world of scarcity and ever-present danger. But here’s the problem: We no longer live in that world. We now live in a world of overwhelming abundance. The access, quantity, variety, and potency of highly reinforcing drugs and behaviors has never been greater, including drugs that didn’t exist before—texting, tweeting, gaming, gambling, sugar, shopping, vaping, voyeuring. The list is endless. Online products with their flashing lights, celebratory sounds, laudatory likes, and bottomless bowls promise ever-greater rewards just a finger click away. They’re engineered to be addictive. The smartphone is the equivalent of the hypodermic needle, delivering digital dopamine 24/7 for a wired generation.

If you haven’t met your drug of choice yet, it’s coming soon to a website near you. Yet despite this increased access to all these feel-good drugs and behaviors—or as I hypothesize, because of it—we are more miserable than ever. Rates of depression, anxiety, physical pain, and suicide are increasing worldwide, especially in wealthy nations.

“The smartphone is the equivalent of the hypodermic needle, delivering digital dopamine 24/7 for a wired generation.”

According to the World Happiness Report, which ranks 156 countries by how happy their citizens perceive themselves to be, people living in the United States reported being less happy in 2018 than they were in 2008. Other countries with similar measures of wealth, social support, and life expectancy saw similar decreases in self-reported happiness scores, including Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Japan, New Zealand, and Italy. Researchers interviewed nearly 150,000 people in 26 countries to determine the prevalence of generalized anxiety disorder, which is defined as excessive and uncontrollable worry that adversely affects their lives. They found that richer countries had higher rates of anxiety than poor ones, and the number of new cases of depression worldwide increased 50 percent between 1990 and 2017. The highest increases in new cases were seen in regions with the highest income, especially North America.

Our compulsive over-consumption has not only led to increased psychological suffering; we are literally consuming ourselves to death. Seventy percent of global deaths are attributable to modifiable behavioral risk factors like smoking, physical inactivity, and diet. There are now more people worldwide who are obese than who are underweight. The poor and undereducated, especially those living in rich nations, are most susceptible to the problem of compulsive overconsumption because they have easy access to high-reward, high-potency, high-novelty drugs at the same time that they lack access to meaningful work, safe housing, quality education, affordable healthcare, and race and class equity before the law. This creates a dangerous nexus of addiction risk.

Our compulsive over-consumption also threatens our planet. The world’s natural resources are rapidly diminishing. Economists estimate that in 2040, the world’s natural capital—land, forests, fisheries, fuels—will be 21 percent less in high-income countries and 17 percent less in poor countries than today. Meanwhile, carbon emissions will grow by 7 percent in high-income countries and 44 percent in the rest of the world.

Throughout my 20-year career, I have seen more and more patients, including otherwise healthy young people with loving families, elite education, and relative wealth, presenting with depression, anxiety, and full-body pain. We are titillating ourselves to death.

“Seventy percent of global deaths are attributable to modifiable behavioral risk factors like smoking, physical inactivity, and diet.”

3. Dopamine fasting.

A patient of mine—a bright and thoughtful young man in his early twenties—came to see me for debilitating anxiety and depression. Having dropped out of college, he was living with his parents and vaguely contemplating suicide. He was also playing video games most of every day and late into every night. Twenty years ago, the first thing I would have done for a patient like this was prescribe an antidepressant. Today, I recommended something altogether different: a dopamine fast. I suggested he abstain from all screens, including video games for one month.

“What?” he said. “Why would I do that? Playing video games is the only thing that gives me any relief.”

“Well,” I said, “let me explain.” That’s when I told him about the pleasure–pain balance, the neuroscience of addiction, and the dopamine deficit state. He was game to give it a try.

He returned a month later and reported feeling better than he had in years—less anxiety, less depression. Why? Because when he stopped bombarding his reward pathway with dopamine, he gave his brain the opportunity to restore homeostasis, a level balance.

He was more surprised than anyone that he felt better. Why? Because it’s hard to see cause and effect when we’re chasing dopamine. It’s only after we’ve taken a break from our drug of choice that we’re able to see the true impact of our consumption on our lives and the people around us.

“It’s only after we’ve taken a break from our drug of choice that we’re able to see the true impact of our consumption on our lives and the people around us.”

4. Self-binding.

My patient returned to playing video games without getting depressed or anxious by keeping the gremlins in mind. First, he restricted his video game playing time to no more than two days per week and no more than two hours a day. That way he left enough time in between for the gremlins to hop off the balance and for homeostasis to be restored. He also avoided video games that were too potent—the ones that once he started, he couldn’t stop. That way he avoided accumulating too many gremlins at once on the pain side of his balance. He designated one laptop for gaming and a different one for schoolwork to keep gaming and classwork physically separated. Finally, he committed to playing only with friends and never with strangers, so that gaming strengthened his social connections. Human connection itself is a potent and adaptive source of dopamine.

I took my patient’s lead. I still watch American Idol YouTube videos, but I try to keep it to no more than two days a week, no more than two hours a day, and preferably with friends and family. As for Dr. Pimple Popper, I avoid that altogether.

How about you? What’s your drug of choice—the thing that once you start, you have trouble stopping, or the thing that makes you feel good in the moment but worse afterward? (Consider the smartphone itself as a possible culprit.) Whatever your drug of choice, I challenge you to give it up for a month, a week, or even a single day. When you do, notice how, at first, your pleasure–pain balance tilts to the side of pain, and you feel restless, cranky, and most of all preoccupied with using your drug. Your brain is screaming out all the reasons why you should use, even though you committed to a period of abstinence. But if you wait long enough and the gremlins hop off and balance is restored, you’ll find that you’re free. Your mind is less preoccupied with using, you’re more able to be present in the moment, and life’s little, unexpected joys are rewarding again. If and when you decide to go back to using, remember to create literal and metacognitive barriers between yourself and your drug of choice so that you don’t go to war with your gremlins. The bottom line is this: To reset your dopamine brain, first abstain.

“To reset your dopamine brain, first abstain.”

5. Pain as a pathway to pleasure.

In the late 1960s, scientists conducted a series of experiments on dogs. Due to their obvious cruelty, these experiments would not be allowed today. Nonetheless, they provide important information on brain homeostasis, or leveling the balance.

After connecting the dog’s hind paws to an electrical current, the researchers observed, “The dog appeared to be terrified during the first few shocks. It screeched and thrashed about. Its pupils dilated. Its eyes bulged. Its hair stood on end. Its ears laid back. Its tail curled between its legs. Expulsive defecation and urination, along with many other symptoms of intense autonomic nervous system activity were seen.” After the first shock, when the dog was freed from its harness, it moved slowly about the room and appeared to be stealthy, hesitant, and unfriendly. Over subsequent electrical shocks, however, its behavior gradually changed. During shocks, the signs of terror disappeared. Instead, the dog appeared pained, annoyed, or anxious, but not terrified.

It whined rather than shrieked, and showed no further urination, defecation, or struggling. Then, when released suddenly at the end of the session, the dog rushed about, jumped up on people, and wagged its tail in what researchers called “a fit of joy.”

With repeated exposure to a painful stimulus, the dog’s mood and heart rate adapted in kind. The initial response (pain) got shorter and weaker. The after response (pleasure) got longer and stronger. Pain morphed into hypervigilance, which morphed into a fit of joy. It’s impossible to read this experiment without feeling pity for the animal subjected to this torture, yet the so-called fit of joy suggests a tantalizing possibility: By pressing on the pain side of the balance, might we achieve a more enduring source of pleasure?

To listen to the audio version read by author Anna Lembke, download the Next Big Idea App today: