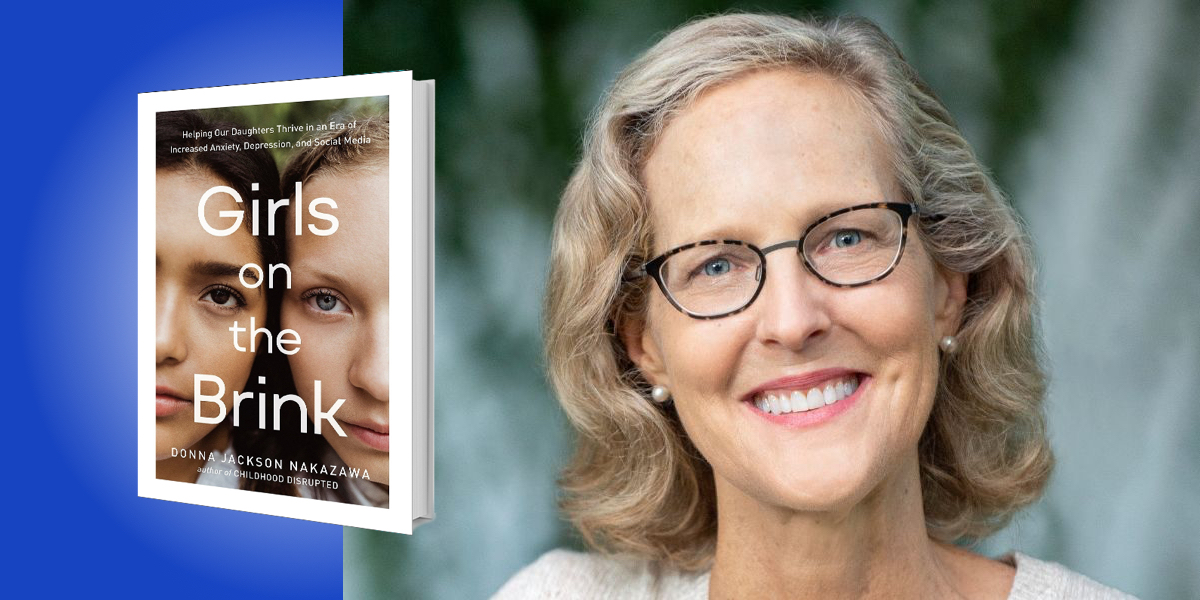

Donna Jackson Nakazawa is an award-winning journalist and internationally-recognized speaker whose work explores the intersection of neuroscience, immunology, and human emotion. Her work has appeared in Wired, Stat, The Boston Globe, The Washington Post, Health Affairs, Parenting, AARP Magazine, and Glamour.

Below, Donna shares 5 key insights from her new book, Girls on the Brink: Helping Our Daughters Thrive in an Era of Increased Anxiety, Depression, and Social Media. Listen to the audio version—read by Donna herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Research into the neurodevelopmental significance of chronic stress and adversity on girls’ mental health is still only recent.

Until just a few years ago, research on how stress affects female mental health was skewed by the fact that these studies originated in male research models. This means that most of what we thought we knew about girls’ mental health as they enter puberty and go through adolescence has been based on the male brain. It was only in 2016 that the National Institutes of Health asked that sex differences be factored into preclinical and lab research and that neuroscientists begin to compare male and female brains in studies looking at mental health and well-being.

Prior to that, regardless of what aspect of mental health was being delved into, the study of female biology was rarely included. It was simply assumed that male models in studies would give results that applied to everyone.

According to the female neuroscientists who are leading this research, the main reason researchers ignored females was that they didn’t want those “pesky hormones” to get in the way of their findings. It turns out that female biology affects how stress is processed by the brain in surprising and powerful ways. This turns out to be particularly true in puberty and adolescence, when girls’ brains are developing fast, and big changes are happening, for good or for ill.

2. We have lost the “in-between years.”

Between the ages of seven and thirteen, children traditionally grew up with more time and space to develop emotionally, socially, and physically without pressure. These years are the bridge between childhood and adolescence, and a lot is happening in the brain during this time. In today’s culture, these years are marked by performance and competition with earlier timelines and higher benchmarks across academics and extracurriculars.

As a consequence, our children are missing that important part of childhood. Those years are when they should be doing things like hanging out with friends and lying in the grass to chat about whatever happens to be on their minds. We have replaced that with a fast-moving culture—and we have now added in social media. Though kids are not supposed to be using social media until age 13, studies show most girls are using it much, much earlier.

“Between the ages of seven and thirteen, children traditionally grew up with more time and space to develop emotionally, socially, and physically without pressure.”

Once girls are on social media, the focus on appearance hits girls especially hard. Their bodies are evaluated based on impossible standards of female perfection. Girls are more likely than boys to receive critical, derisive, sexist messages about their body, face, and appearance. This has a particularly strong effect on girls as they scroll, stare, compare and despair, and feel they don’t measure up.

As one girl told me “if you want to be popular at school you have to first be popular on Instagram, which means you have to be willing to be sexualized as if you’re an adult woman, even if you’re just a kid.” Add to this background threats of global warming and school shootings. All of this is layered on top of the stark reality that girls routinely face added threats like sexual harassment, rape, and violence against women by virtue of growing up female. The kicker here is that this early exposure to external judgment, hierarchal evaluation, and critiquing is happening during the most vulnerable window in brain development.

3. Stress has unique consequences for girls as puberty begins, which now happens earlier.

Puberty is a super vulnerable time for girls’ brain development. Of course, this is true for boys, but it is especially true for girls. When estrogen comes on board during puberty, it is particularly powerful at increasing a potent stress response to unmitigated chronic stressors.

Estrogen, evolutionarily speaking, is a very groovy hormone and master regulator in the brain. In normal circumstances, it gives women an added immune response that helps keep them healthy and strong. Estrogen enhances all the body’s systems and organs including the brain.

However, when females face big ongoing stressors in the environment, estrogen can amp up the body’s stress-immune response in a way that testosterone does not. Estrogen can flip from an evolutionary advantage to a disadvantage. This is why women suffer from autoimmune diseases at several times the rate of men. It’s also why more women suffer from long Covid.

At puberty, the brain factors in all the social and emotional stressors you’ve ever faced in your life and rewires the brain based on that intel. This is why at puberty we begin to see differences emerge in girls’ health. When girls experience overwhelming social and emotional stressors at the same time that estrogen is coming on board, this can exacerbate the ill effects of stress on health and development.

“Estrogen can flip from an evolutionary advantage to a disadvantage.”

On top of all that, girls today are going through puberty at younger ages, at a time when the brain isn’t supposed to be remodeled. This really matters in terms of girls’ mental health. The parts of the brain that help discern how to respond to social and emotional threats, put them in proper context, and how and when to ask adults for help, have not wired and fired up yet. This means they are having feelings and experiencing adult-like layers of stress before their brains have developed the scaffolding for resilience.

4. Social and emotional threats exact an especially high cost on our bodies and brains.

The brain is really a detective. Across childhood and into adolescence, a child’s brain is dancing with cues and messages from the environment to try to answer one question: am I safe or am I not safe? To really understand this, we have to take a step back in time.

Early in human history, survival depended greatly on close collaboration and cooperation within the tribe. Being left out, made fun of, dismissed, or excluded by others meant you would be the last person to get meat from the communal fire or be given other nutritious food. At the outskirts of the tribe, you would be more easily attacked: you might not hear the call of alarm if a predator or warring tribe were nearby. Being slighted or gossiped about might also be a warning sign that you’d soon be entirely ostracized, which would make you more vulnerable to physical harm: no food, shelter, or help if you needed it. It could mean that suddenly you may be outside of the tribe’s protection. If you were exposed to the elements or predators, you were also more likely to be wounded, and to develop infection.

Given the ill effects that could follow even a small social slight, it made sense that over thousands of years, our immune system evolved so that in the face of social threats, it preps us for the possibility of coming physical danger. This is why social stressors can evoke an immune response that’s very similar to that of experiencing physical harm.

George Slavich, a professor at UCLA, has coined a useful term for this: Social Safety Theory. What this means is there is an evolutionary mismatch between the unique pressures and stressors girls face in modern life and our deep and longstanding evolutionary wiring in the brain. Being dissed at an early age on social media might not be physically dangerous, but to the brain—especially the adolescent brain—it feels as if it is.

5. We must bring down every girl’s body and brain stress machinery, while also making sure we are creating deep connection.

The female body and brain are more susceptible to being adversely affected by chronic stress only when its source remains unmitigated in the environment. Even a well-loved girl’s sense of who she is can diminish over time amid an avalanche of modern stressors and sexist messaging.

“Girls’ brains at puberty are incredibly agile; they are taking in and processing a lot of social cues at once.”

Remember, in healthy supportive environments, puberty and adolescence are a time of potential and promise. When girls feel safe, their stress machinery is less likely to get engaged, or set on overwhelm. When they feel safe, they have a better chance at getting through their teen years without depression or anxiety. Girls’ brains at puberty are incredibly agile; they are taking in and processing a lot of social cues at once. If these messages encourage healthy connection and are empowering, if we eliminate a lot of the toxic stressors girls now face, the adolescent female brain is an absolute superpower.

As parents, we don’t always have insight into our daughters’ states of mind, and studies bear this out. As our daughters face more stress before their brain is equipped to make sense of so much overload, they often don’t know how to ask for our help.

There is an art and a craft to communicating with girls in neuroprotective ways, and to setting up the support scaffolding they need from their larger community. When your daughter comes to you with hard things, make it a good experience for her. Researchers at Johns Hopkins have found that girls were 12 times more likely to flourish when families were able to answer yes to just one question: Can your child come to talk to you about anything, no matter how difficult?

Teens only voice themselves when they feel heard. The best way for them to feel heard is to listen more, talk less, and offer less advice. Try not to jump in as the fixer or the detective.

If your daughter comes to you with a problem and asks what you think, try saying something like, “I promise I’ll tell you what I think, but first, I really want to know what you think, because what you think right now is more important than what I think.” This gives her time to process her thoughts and spill what’s really bothering her, helping her to feel seen, safe, valued, and heard. She will learn that she matters, while deepening her connection to you, and also helping to foster deep connection and healthy and crucial neural wiring in her brain.

To listen to the audio version read by author Donna Jackson Nakazawa, download the Next Big Idea App today: