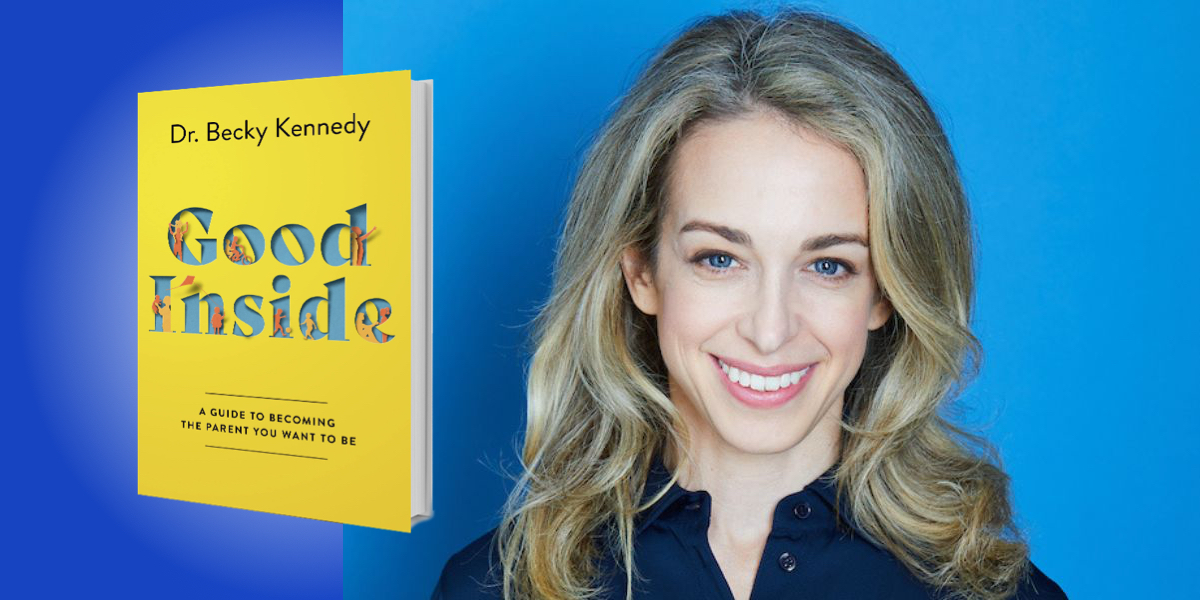

Dr. Becky Kennedy is a clinical psychologist and a mother of three. She is the founder of Good Inside, a learning resource for parents and she was recently named “The Millennial Parenting Whisperer” by TIME magazine. She hosts a podcast of the same name, Good Inside.

Below, Becky shares 5 key insights from her new book, Good Inside: A Guide to Becoming the Parent You Want to Be. Listen to the audio version—read by Becky herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Most generous interpretation.

Let me share an assumption I have about you and your kids: you are all good inside. The foundation of seeing people as good inside allows for curiosity about their not-so-good behavior. If we believe people are good inside, then we can see bad behavior as a sign of struggles, not as a sign of who they are. But seeing others as good inside is hard. It’s remarkably easy to put anger and frustration in the driver’s seat with questions like, Did my kid really think he could get away with lying to my face? Does he think he can get away with that? instead of, I wonder why my kid lied to my face? What was too scary or overwhelming to tell me? and then, for bonus points, What has my child picked up from me that leads him to think he can’t tell me these things?

Parenting from a Good Inside perspective takes practice, and in this practice, we can use a little hack. When you think about a behavior in yourself or your child that brings up anger, frustration, and maybe judgment, take a breath and ask yourself, What is the MGI (Most Generous Interpretation) of this behavior? The LGI (Least Generous Interpretation) comes up much more easily. For example, when my son hits his sister, my LGI might be, “he’s so cold-hearted,” while my MGI could be, “It’s hard to share toys.”

Using an MGI doesn’t make a bad behavior OK. It just helps you see the good kid or adult who is under the behavior. This encourages intervention from a place of seeing our kid as a good kid having a hard time, not a bad kid doing bad things. This mindset difference is everything.

2. Know your job.

In any system, clearly defined roles and responsibilities are critical to ensuring that things run smoothly. The opposite is true as well: systems break when members are confused about their roles or impinge on other people’s functions. Family systems are no different, and every member has a job.

“Our kids should not dictate our boundaries, and we should not dictate their feelings.”

Parents have the job of establishing safety and connection through boundaries, validation, and empathy. Children have the job of exploring and learning through experiencing and expressing their emotions. We all have to stay in our lanes: Our kids should not dictate our boundaries, and we should not dictate their feelings.

A boundary is a decision or a limit from a parent. Boundaries tell a child what a parent will do and require a child to do nothing. This is key: a boundary is not Stop jumping on the table. Get off! but rather, If it’s too hard for you to get off the table, I will pick you up and place you down, and following through if your child persists. Validation is the process of seeing someone else’s emotional experience as real and true, and empathy is our ability to understand and relate to other people’s feelings.

Here is an example of parents and kids doing their jobs. Your child is protesting, pleading, “Please 15 more minutes!” — remember, they aren’t being difficult, they are doing their job of expressing themselves. Doing your job would be saying, “Two things are true: iPad time is over and you’re allowed to be upset. It’s so hard to end things we enjoy. For me too.” Your child may still protest, and that’s OK. No one is having fun, but you are both doing your jobs well.

3. It’s never too late.

There’s one question I hear from parents more than any other: Is it too late? Have I messed up my child? My answer is always No.

There is no such thing as a perfect parent. All parents have moments that feel “off” with their kids: where they lose their cool and yell words they wish they could take back. Deep breath. All Parents have been there. The fact it happened isn’t the issue, the key is what happens next. Parenting doesn’t have to be defined by moments of struggle. It should be defined by whether or not we connected with our kids after the struggle.

There’s no one right way to repair, though there are baseline to-dos: Say you’re sorry, share your reflections, and say what you plan to do differently in the future. It’s important to take ownership of your role instead of insinuating that your child “made you” react a certain way.

Here’s a sample script to bring all of these elements together: “I was having big feelings that came out in a yelling voice. Those were my feelings and it’s my job to work on managing them better. It’s never your fault when I yell. I love you.”

“Parenting doesn’t have to be defined by moments of struggle.”

Repair can happen ten minutes after a blow-up, ten days, or ten years later. Never doubt the power of repair. Every time you go back to your child, you allow him to rewire and rewrite the ending of the story so that it concludes in connection, safety, and understanding, rather than aloneness, fear, and self-blame.

4. Resilience over happiness.

Don’t you just want your kids to be happy? I’m asked this all the time. And honestly, the answer is No. To be clear, I am not wishing for my kids to be unhappy, but a focus on happiness in childhood tends to lead to an adulthood filled with anxiety.

I’ve never had an adult come to my private practice and say, “Well, my parents were just such great parents that well… They got rid of all the hard feelings. I only feel happy!” But I have had hundreds of adults show up with essentially no coping skills for hard feelings. They are no better off at age 35 than when they were in early childhood regarding their ability to regulate frustration, jealousy, disappointment, sadness, and not-good-enough feelings.

Happiness is less compelling than resilience. After all, cultivating happiness is dependent on regulating distress. That’s the big paradox: the more able we are to regulate hard feelings, the more space there is in our bodies to generate happiness. So how can we help our kids build regulation skills early on for the best chance of cultivating happiness later on?

Let’s say our kid comes home from school upset about not being invited to a slumber party. If we focus on a flight to happiness, we’d say, “Well you don’t even really like her anyways! It’s fine! Let’s plan our own slumber party that night. You can invite Keala and Aura and Pia.” If we focus on building resilience, we’d say, “I’m so glad you’re talking to me about this. It stinks to feel left out. I know.” And then pause to see what happens next. Maybe you share a story of being left out. Maybe your daughter eventually wants to plan her own slumber party—not from a place of avoidance, but as something that comes after feeling like it’s OK to feel sad and disappointed. This builds your child’s tolerance to sit with upset feelings because you’ve modeled that you are able to sit with this feeling.

“The more able we are to regulate hard feelings, the more space there is in our bodies to generate happiness.”

We want to prepare our kids to cope with emotions, not protect them from emotions they will inevitably experience. Resilience over happiness.

5. Tell the truth.

This might sound like a silly principle, but telling the truth is surprisingly tricky to put into practice with our kids. After all, parents often fear that telling their kids the truth will be too scary or overwhelming, but we tend to have it all wrong when it comes to what scares children. Feeling confused and alone in the absence of information is what terrifies children.

Children are wired to notice changes in their environment (Why do my parents look sad? Why is everyone saying the word funeral?), and kids are wired to perceive changes as a threat until an adult helps determine that they are safe. Blame it on evolution: for our species to survive, a child had to assume a rumbling in the forest was a bear until an adult confirmed it as a squirrel. The child registers fear until an adult is present to explain. Even if a parent confirms “the worst,” a child will feel safer knowing that they are not alone because an adult is with them in their scary reality. A supportive, honest, caring presence feels safe to children and makes difficult truths manageable.

Let’s take an aunt’s death. You wonder whether your 4-year-old can understand this, but with this principle in mind, telling the truth might sound like this: “I want to talk about something that we are all going to have big feelings about. Aunt Sally died today. Do you know what that means, die or death? Death is when someone’s body stops working.” …“There are a lot of other details we can talk about, but first, I want to pause. See how you’re doing.” … “You didn’t do anything to cause this. I’m not dying. I’m here. I’m healthy. We are still a family.”

To listen to the audio version read by author Becky Kennedy, download the Next Big Idea App today: