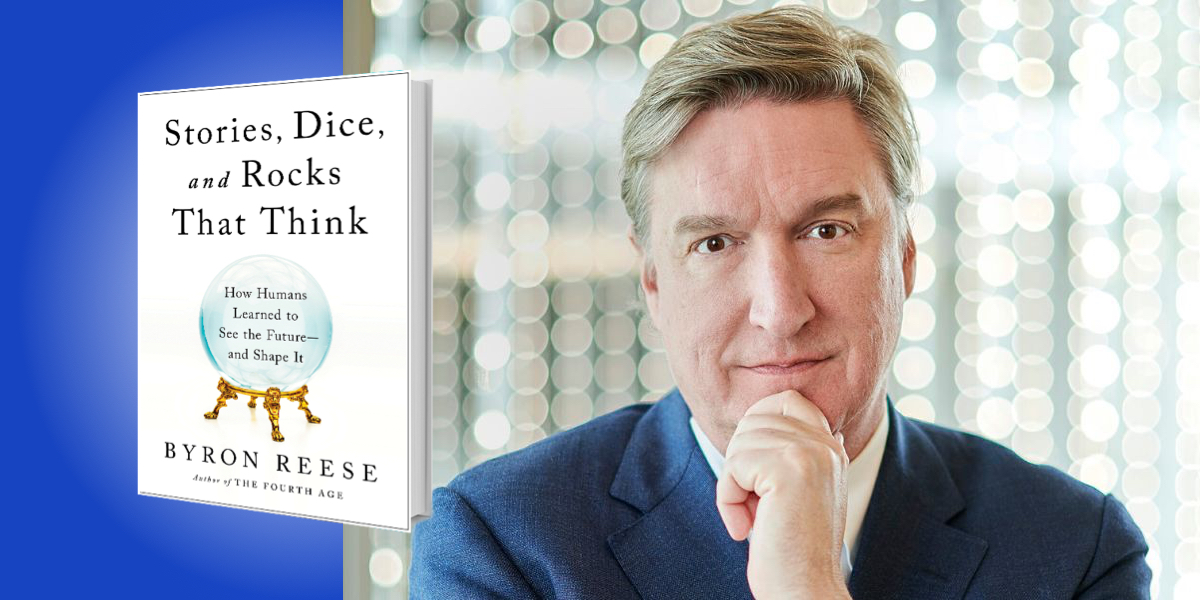

Byron Reese is an Austin-based entrepreneur with a quarter-century of experience building and running technology companies. A recognized authority on AI, he holds a number of technology patents. In addition, he is a futurist with a strong conviction that technology will help bring about a new golden age of humanity. He gives talks around the world about how technology is changing work, education, and culture. He is the author of four books on technology.

Below, Byron shares 5 key insights from his new book, Stories, Dice, And Rocks That Think, How Humans Learned To See The Future And To Shape It. Listen to the audio version—read by Byron himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. The Acheulean hand axe.

For about 2 million years, a creature called Homo erectus, thought to be an ancestor of ours, roamed over Asia, Africa, and Europe. Erectus had one tool that they knew how to make. It was called an Acheulean hand axe, and it looks something like a big arrowhead, but in a teardrop shape. Homo erectus made so many of these, in fact, that you can buy one on eBay, an actual tool used a million years ago, for about a hundred dollars.

Here’s where it gets interesting. If I were to show you two hand axes made a million years apart, and ask you to tell me which one was older, you’d have a hard time doing it. Even experts are only able to date them within 500,000 years.

How can that be? How is it that all Acheulean hand axes we have found look nearly identical? If every Homo erectus was just copying their parents’ hand axe, they would drift over time and place. The ones that we would find a hundred thousand years later in Asia would look different than the ones we find in Africa. But that is not the case.

The conclusion we can draw from this is that the hand axe was not a piece of technology. Nor was it a cultural object. It was a genetic object. So just like a given species of bird will make the same nest no matter where they are over long periods of time, or beavers will build the same dam using the same techniques no matter where they are, Homo erectus only knew how to make this tool. Homo erectus probably didn’t even know what it was doing while it was carving this thing. Otherwise, how could it have gone 86,000 generations without ever making any improvements?

What this teaches us is that Homo erectus were nothing like us mentally. Physically, perhaps they are our ancestors, but mentally they have nothing in common with us. They only had that one tool, which they knew how to make genetically. Yet we invented technology that we improve, and improve, and improve. And that’s why it only took us three generations to get from Kittyhawk to the moon.

2. Becoming us.

On cave walls in Europe, Asia, Australia, and Africa, you can see art originating all the way back to the paleolithic era. If you look at some of the oldest cave art that we know of, in a cave in Chauvet, France, dating to 30,000 BCE, you’ll see that the paintings are beautiful—absolutely stunning. Now, if somebody had asked me, what do you suppose the evolution of cave art was like, I would have said, well, I’m sure a long time ago, there were these stick figures we drew on the walls, then later we put a little triangle on them to represent a dress, and then later still scrawled some hair, and eventually, it got better and better. But that’s not what the record shows.

“The primary purpose of language is to think with, not to communicate.”

The record shows nothing, nothing, nothing… and then Chauvet, out of the blue. As if that weren’t enough, at that exact same time, we find the first representative art, art like a carving that is something other than just shapes—a carved woman, a carved lion, et cetera.

Interestingly, the earliest musical instruments we have are also from that exact time. So somehow it looks like we were going on and on, without cave art, without musical instruments (that we can detect), without representative art…and then one day we got it all. What happened?

It’s almost as if a radioactive spider bit us, and I think (metaphorically), that’s largely what happened. Something happened to humans between 50,000 and 70,000 years ago, just some small change in their brains, that gave them symbolic language. It gave them a way to think. The primary purpose of language is to think with, not to communicate. And those people with that tiny mutation had an enormous advantage over everyone else.

Those people are our ancestors. It explains why we went millions of years with no technological improvement. And then overnight, we seem to have emerged fully us.

3. Probability.

I’ve always been fascinated by how the future happens. Why does one thing happen and not another? There have been a lot of theories about this. Some people believe that things were destined to happen, that it had been pre-written that they would happen.

Another theory is that things happen out of necessity—a slightly more scientific view. That if A causes B causes C causes D, then every single thing that has happened to you, even you stubbing your toe this morning, was the inevitable outcome of a series of events stretching back to the big bang. It could have happened no other way. And if you rewound the universe and started it over again, you would stub your toe again this morning.

Other people believe in something called synchronicity. This is the theory that everything in life is connected to other things. That’s why, supposedly, you can study the entrails of a chicken or look up at the stars and understand something about the future. It’s because it’s all connected.

Another view is that the future unfolds because of the will of people. People, individuals who act, that is the driving force.

Yet the thing that people didn’t guess was largely what happens—probability. For example, if I were to ask you, if you flip a coin a thousand times, how many times will it come up heads?

“[We are able to predict the future,] not by knowing what will happen, but by knowing that in large amounts of random events we get predictability.”

You might say, “Probably about 500.” And you would be right. The odds of it being under 400 or over 600 are one in many billions. It just won’t ever happen, no matter how many times you do it.

And that’s a really big idea, that something random, that is the flipping of a coin, has that high degree of predictability. That simple idea underpins probability, and it is how we are able to predict the future. Not by knowing what will happen, but by knowing that in large amounts of random events we get predictability.

4. DNA.

For millions of years, the only place we’ve ever had to write information was in our DNA. It took millions of years to write one thing. While it was very slow, it was also pretty reliable. That’s how the Monarch butterflies can make it from a milkweed plant all the way to Mexico, and back to the same milkweed plant. Because it’s in their DNA.

Somewhere along the way, maybe 70,000 or 80,000 years ago, we got symbolic language. It gave structure to our thoughts, and we could now think in language. Thanks to this development, we could now write information in two places: In our DNA over the long term, and in our heads over the short term. So instead of us having to evolve knowledge not to eat the purple berries, somebody could just say, “Hey, don’t eat those purple berries.” Then he would know, and that mutation—knowing not to eat those berries—could spread instantly. And that ability is what supercharged our development as a species.

There was an essay written over half a century ago called “I, Pencil.” In it, the author pointed out that nobody knew how to make a pencil. There was nobody on the planet who could mine the iron ore and smelt it into steel, harvest the wood, make the paint, and all the rest of it. Yet a pencil gets made. Why?

Because it’s in the DNA of the species. It’s in all the written instructions spread through the minds of a thousand different people. All of a sudden, we have become essentially a superorganism that knows how to make pencils.

That’s nothing compared to what we can do today. Your body has something on the order of 30 or 40 different elements in it. A smartphone has 60. And the supply chain that makes that smartphone is almost impossible to fathom, how all those elements come together to make that phone that you then buy and use. It’s the same principle. Nobody knows how to make a smartphone, but collectively the superorganism, which I call Agora, does. That’s how smartphones get made.

5. Our collective memory.

I think the story of our species is how slowly we’ve developed. In large part, it’s because somebody had to learn something, remember it, and tell somebody else. Then that person had to remember it. If they died, maybe somebody else remembered it—and maybe somebody didn’t And so an enormous amount of knowledge must have been lost, as the moment anybody died, a lifetime of learning potentially died with them. But is there any way out of that?

In the age of artificial intelligence, where we’re using computers to look for patterns in data, we’ve learned a trick that might help us get beyond this slow development. It works a lot better if you can figure out a way for the computer itself to collect the data because then the data’s clean. With the data that the computer collects, it can use it to train its model.

“It would be a remarkably different world if you could make informed decisions about everything you do.”

If the computer can get its own data at some scale, then it’s essentially on its own. So imagine a future where every single thing you did was logged: Every word you said, everything you looked at—whether your eyes dilated when you did—everywhere you went, every bit of the caloric and nutritional information of every bite of food you ate, every heartbeat, every breath.

Now, if you were able to do that for, say, a hundred years across the entire planet, you would have a knowledge base of everything. Everything that everybody had tried and failed at, everything that they had tried and succeeded it—for all of humanity. By mining the data, we would make real progress. Because we aren’t on our own any longer. The collective experience becomes the data, which makes every individual life better.

Of course, there are many ways that this can go wrong. It would be up to us to figure out how to get the benefits of it without all the bad that can come with it. But the benefit is probably worth it. It would be a remarkably different world if you could make informed decisions about everything you do. You don’t have to make that decision, but just knowing the right thing is a big step forward.

We always say that knowledge is power. The real power is to make your life better. And I think we’re going to build that system one day, and use it to make a great and glorious future.

To listen to the audio version read by author Byron Reese, download the Next Big Idea App today: