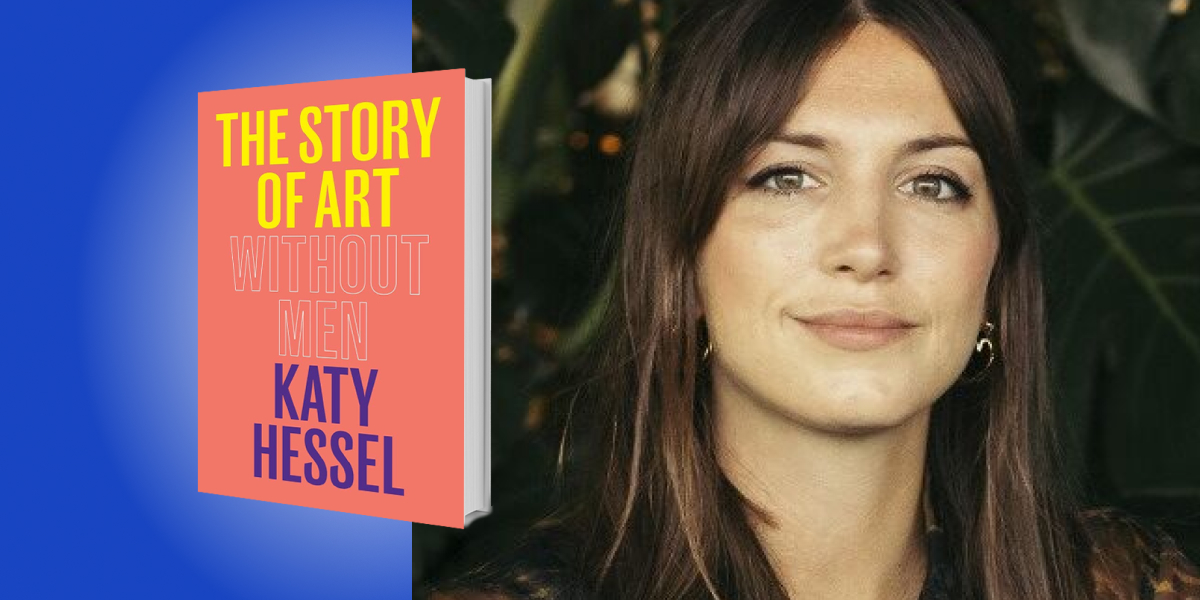

Katy Hessel is an art historian, broadcaster, and curator dedicated to celebrating women artists from all over the world. She runs The Great Women Artists podcast, where she has interviewed the likes of Tracey Emin, Marina Abramovic, and authors Ali Smith and Deborah Levy. She has lectured at Tate and National Gallery, presented films for the BBC, and is a Visiting Fellow at Cambridge University. She is also a columnist for The Guardian.

Below, Katy shares 5 key insights from her new book, The Story of Art Without Men. Listen to the audio version—read by Katy herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

While studying the work of Alice Neel, an American portrait artist, at university, it was the first time I really thought about the underrepresentation of women artists. Alice Neel not only fought to be a portrait painter amongst those working in post-war New York City when abstract expressionism and minimalism were all the rage, but she also worked as a woman in a male-dominated field.

Alice was also the painter of the late and great feminist art historian, Linda Nochlin. Nochlin penned the essay “Why have there been no great women artists” at the dawn of the feminist movement in the January 1971 Issue of Art News.

But my idea really came into existence after visiting an art fair in October 2015. When I walked into that tent, looking at all the artworks in front of me, I realized that not a single one was by a woman artist. This prompted me to ask myself a series of questions: Could I name 20 women artists off the top of my head? Could I name any prior to 1950, or any from before 1850? The answer was no. I had essentially been looking at the history of art from a male perspective. I was shocked and decided to start an Instagram blog. This would not only challenge me to find a different woman artist every day, but it was a way to put my knowledge to good use. It was also a way to tell stories about those artists who had often been overlooked by the museums and the galleries.

When listing the artists who are typically said to define the art historical canon, it’s the following names that come up: Giotto, Titian, Leonardo, Caravaggio. But what about Gentileschi, Kauffman, Powers, MacDonald, Macintosh, Valadon, Hoch, Asawa, Krasner, Mendieta, Pindell, and Himid. If I hadn’t actively been studying women artists for the past eight years, I doubt I would even know more than a fraction of these.

But should any of this be surprising? Not according to statistics. In London, the National Gallery’s collection is made up of just one percent of women artists. The Royal Academy of Arts, in its over 250-year history, is yet to have a solo exhibition by a woman artist in its main galleries. The Turner Prize, which is one of the most prestigious prizes in the world, took until 2017 for the first woman of color to ever win. When we think about how we place a monetary value on genders in society, art prices reveal just that. A woman artist on average today in the Western world goes for just 10 percent of her male artist contemporary.

My work, in general, is not just about breaking down the gender imbalance or about breaking down the hierarchy between art forms saying that textile is equal to painting, sculpture is equal to architecture, and pottery is equal to monumental work. Nothing should be hierarchical. I want to break down the stigma around elitism in art history. By adopting an accessible style, I hope to appeal to anyone of any art historical level who is interested in learning about the stories of overshadowed artists.

1. Artemisia Gentileschi painted in a man’s world.

Artemisia Gentileschi was born in 1593 in Rome. She was associated with the Baroque movement, which came to fruition in the 17th century. The Baroque movement was infused with stunning light effects, often showing biblical narratives for the purpose of getting people back into the Catholic church.

“Back then women artists didn’t even have access to the life room where they could study the nude form and learn anatomical accuracy until 1890.”

In her lifetime, Gentileschi became an international celebrity. She had the advantage of being raised in an artistic family, growing up in her father’s studio in Rome. Back then women artists didn’t even have access to the life room where they could study the nude form and learn anatomical accuracy until 1890.

Gentileschi signed and dated her first large-scale painting when she was just 17. It was called “Susanna and the Elders” and it recalls the tale of a young, virtuous woman who was bathing in her garden when two men try to seduce her. She fills her viewers with discomfort and anguish, but she captures the tense moment when Susanna shields her body away from the intruders, perhaps showing what life might have been like as a woman.

Gentileschi was an international celebrity in her time. She even had people paint pictures of her hand so they could feel like they were closer to her absolute genius. She made fantastic works of biblical heroines such as Judith, Lucretia, Susannas, and more. She also upended all we knew in our history. One of her famous quotes from 1649 is “I’ll show you what a woman can do.”

2. Harriet Powers quilted masterpieces.

Harriet Powers appears in the 19th century as a quilt maker in America. Now, art historians have overlooked quilt making as a key medium for far too long. No doubt, this is a result of the hangover from the academies and the 18th century who dismissed embroidery as craft. Quilt making is important artistically, but also as a political tool and medium which women have dominated.

Harriet Powers was extraordinary. She was enslaved in Georgia and it is thought that she, like most quilt makers, learned sewing from her female family members. She received prizes for her narrative-driven quilts with complex cut-out and applicate figures. She honed her art on an even more ambitious scale, and, in 1895, made her most innovative work pictorial quilt. This monumental quilt comprises 15 densely-packed scenes, which recount a mix of Bible stories and miraculous legends.

While we can only imagine why she chose to document these tales, we know her quilts were made for the purpose of being displayed, rather than used practically. Despite her impressive quilting abilities, she remained largely unknown to the public until the 1970s.

3. Suzanne Valadon epitomized modernity.

Valadon was working at the dawn of the 20th century in Paris. Modernity was in the air and women had more freedoms than ever. They could now enter the life room and draw from the nude. They could travel unchaperoned and have some independence.

What makes art modern? What does modern art mean anyway? Modern art is a break from the past, the eradication of hierarchies, lines shattered on a canvas, and scenes of everyday subjects of modern society. You could say all of those things, but what makes art modern is the participation of women artists.

Women were no longer confined to working in the traditional realm under the guard of or dependent on men. They turned their gaze onto themselves, claimed spaces of their own, embraced sexual freedoms, and expressed as they had never done before.

“What makes art modern is the participation of women artists.”

One woman who had epitomized this modernity was Suzanne Valadon. Nothing about her was conventional. She created taboo-breaking paintings, which portrayed herself nude and her style encompassed the colors of post-impressionism with the wildness of the fauves. Her subjects exuded fierce independence.

She began her career as a circus performer, but her acrobatic dreams were cut short after an accident at the age of 15. She then turned to artist modeling, sitting for the likes of Degas and Toulouse-Lautrec. She in turn taught herself how to paint, watching those who would actually paint and draw her.

She had her first solo exhibition at age 46, and in the early 1920s made a work called “The Blue Room” which upends the Venus-like pose that we’ve so often seen in art history. It’s a self-portrait of her as both an artist and model. She’s wearing green stripe trousers and a loose strapped, pale pink top. She lies on her bed, framed by a sea of rich blue floral fabrics and a cigarette hangs out of her mouth. She has pushed a collection of books to the back of her bed and she exudes self-assurance. She has control of her brush, her image, and her life. She is showing that in the 1920s, a woman could do whatever she wanted.

4. Augusta Savage sculpted for the world.

Another woman working at a similar time to Valadon was the acclaimed artist, Augusta Savage. She was right at the center of Harlem in the 1920s and 1930s, home to the epicenter of Black cultural creativity known as the Harlem Renaissance.

Savage was raised in a strict family in Florida and arrived in New York City with just $4.60. She mastered emotionally tender and stoic life-size figures and portrait busts painted with shoe polish for that bronze effect. Savage, despite not having much money at that point, used this shoe polish in such an innovative way as to actually create the bronze effect.

Savage was an advocate for equality, in particular education, having herself been denied a scholarship to study in France because of her race. She was soon able to travel to Paris to witness the splendors of the Avantgarde.

“Imagine the impact this work would have had on the world now and beyond.”

But her breakthrough really came in 1937 when she was commissioned by the 1939 World’s Fair to make a sculpture reflecting the contribution to music by African Americans. It was a work that was originally 16-foot-high, placed in the middle of the World’s Fair. It portrayed an elegant heart-shaped choir of black children whose bodies stand in the palm of God’s hand. It earned Savage national press coverage. Although photographs of the work still survive, the sculpture itself was destroyed after the fair due to the lack of funding to pay for its storage. Imagine the impact this work would have had on the world now and beyond.

5. The women artists of today are many.

As we follow the history of women in art to today, we can find them in every movement in Western art history. During the Harlem Renaissance, at the forefront of the Great Depression, we can find women street photographers. We find women artists during the periods of abstract expressionism and minimalism. There are a slew of women pop artists, as well as participants in the neo-concrete movement in Brazil.

When we look at the feminist movement, we look at the eighties with the likes of Jenny Holzer, Cindy Sherman, Francesca Woodman, and Carrie Mae Weems. In the nineties and the 2000s, we find the new masters of art of our modern times. These are all artists born in the nineties, who were spearheading the new representation of oil: Jadé Fadojutimi, Flora Yukhnovich, and Samaya Critchlow.

To listen to the audio version read by author Katy Hessel, download the Next Big Idea App today: