Brett Scott is a journalist and financial hacker who writes about the intersection of money and digital technology. His work can be found in publications such as the Guardian, New Scientist, Wired Magazine, and CNN.

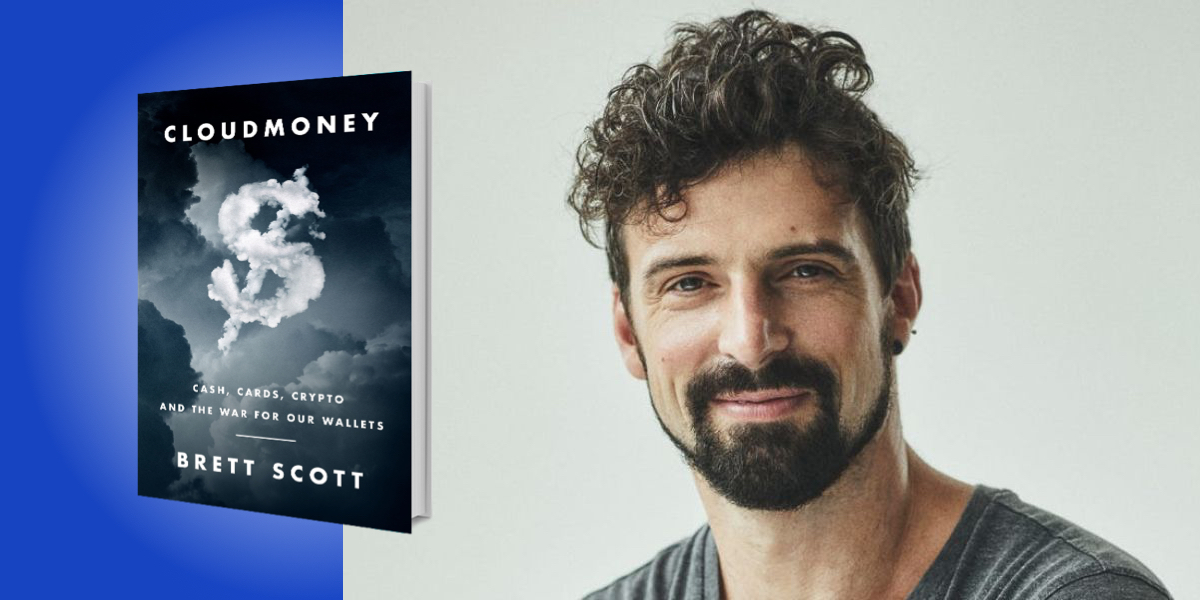

Below, Brett shares 5 key insights from his new book, Cloudmoney: Cash, Cards, Crypto, and the War for Our Wallets. Listen to the audio version—read by Brett himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. The US dollar is three different currencies with the same name.

We are often led to believe that digital payments are an advanced upgrade to physical cash, but this is deeply misleading. We live under a hybrid monetary system with at least three different forms of money that symbiotically interact with each other. The first is physical cash issued by government institutions, like the Federal Reserve. The second is digital dollars issued by banks. The third is issued by corporations, like PayPal.

Picture me walking into a casino and handing over $100 in government cash for $100 of casino chips. The casino took ownership of my cash while issuing a form of private money—casino chips—to me. There are two forms of money here: government cash and privately-issued casino chips that can be redeemed for government cash.

This image of privately-issued chips is very useful when trying to understand the banking sector. When you deposit cash at a bank, they take ownership of your cash and issue you “digital chips” that can be used within the confines of the bank payments system. They can also issue far more digital chips than they have in government cash, and a huge amount of what we call “money” is actually issued by commercial banks in this form. Players, like PayPal, can take ownership of your bank-issued chips, and issue you their own chips.

2. “Cashless society” is a euphemism driven from the top down.

A “cashless society” is one in which we become totally dependent upon bank-issued and corporate-issued digital chips. Calling this a “cashless society” is like calling whiskey “beerless alcohol.” It’s evasive. I was recently at a “cashless” pub in London, and to pay for a single small item I had to download an app that required interacting with at least three mega-corporations. I was supposed to use Google or Facebook for identity, two commercial banks for the digital money, and Visa or Mastercard as the means for messaging those banks. “Cashlessness” is a euphemism for a distant conglomeration of data-hungry, profit-driven corporations that seek to get between me and those I’m trying to pay.

“A “cashless society” is one in which we become totally dependent upon bank-issued and corporate-issued digital chips.”

The move towards a cashless society is presented as though it were driven from the bottom-up through consumer choice. The truth is that there has been a top-down war on cash for decades, driven by institutions that want to make it more likely that we will choose digital payment. These include banks, payments companies, fintech companies, big tech, and even governments. The commercial players have two goals: make profit and get data. The political players have one goal: increase control.

3. Physical cash is the bicycle of payments.

People often speak of convenience as though it can be increased indefinitely through more technology. Supposedly, we’ll get more leisure as technology progresses, but in reality, we are busier than ever.

Convenience is a relative concept. Imagine a person on the outskirts of Los Angeles contemplating how to get to their workplace 10 miles across town. In this context, walking appears inconvenient, and having a car appears convenient, but ask yourself why this person lives 10 miles from their office to begin with. It’s because of cars. In capitalist economies, technologies are seldom used to increase leisure. Rather, they are used to expand and accelerate the economic system. Once that happens, our environments get recalibrated. A person on the outskirts of Los Angeles is not liberated by the automobile industry providing convenience. They are captured by the industry’s structural choke-hold over their lives.

“Cash is like the public bicycle of payments, allowing for peer-to-peer, localized, and resilient transactions.”

Just like we find millions of people “choosing” to buy cars in an urban environment that has been altered by the car industry, so too will many people experience themselves “choosing” to use digital payments in an economy dominated by big finance and big tech. Those industries have far more to gain from digital payments than we do, and the “convenience” they offer is predicated upon us becoming dependent upon their power. In this context, the digital payments industry presents cash as the horse-drawn cart of payments, an outdated form that’s clogging up the economic highways. In reality, cash is more like the public bicycle of payments, allowing for peer-to-peer, localized, and resilient transactions.

4. Fintech isn’t revolutionizing finance—it’s just automating it.

After the 2008 financial crisis, entrepreneurial technologists claimed that digital technology could disrupt and democratize finance. Fintech companies presented themselves as revolutionaries, but they seldom wanted to make deep-level reforms to the financial system. They just wanted to make the same old system faster and more automated by designing apps that could be pasted over it. Rather than interacting with service staff in a bank branch, we are encouraged to do self-service via phone. Fintech also moved into automating the jobs of bankers. Instead of a human assessing your loan application, an algorithm will do it.

This is why the fintech industry is anti-cash. Offline cash is hard to integrate into automated systems, so the fintech sector presents cash as outdated. These so-called revolutionaries have slowly but surely merged into the incumbent financial system. Banks have a strong drive to automate, so they began absorbing fintechs. On average, the fintech sector has cut costs for the banking sector and thereby enabled it to spread into parts of society that were previously insulated from it. This often gets called financial inclusion, but people are being included into data-hungry corporate systems with huge power dynamics.

“Bitcoin is a system that allows vast networks of strangers to issue tokens and move them between themselves without banks.”

Simpler, slower, and smaller systems can be far more resilient and inclusive than complex, fast, and large-scale digital ones. Rather than uncritically hopping upon the fintech bandwagon, we should ask ourselves how to balance between digital and analog systems.

5. Bitcoin doesn’t challenge the monetary system.

In the nineties, a group of activists known as cypherpunks experimented with building alternative forms of digital cash to act as a counterpower to the banking sector. In 2008, a person or group under the pseudonym Satoshi Nakamoto took a range of cypherpunk innovations, combined them into an elegant recipe, and called the result Bitcoin. It’s a system that allows vast networks of strangers to issue tokens and move them between themselves without banks. Bitcoiners claim that this can save us from the vortex of big tech, big finance, and big governments.

I was involved in the early Bitcoin community but quickly realized that the system was a sophisticated means for moving crude tokens. The innovative technological architecture tricks people into believing that the tokens are sophisticated too, but really, they are limited edition digital objects that are merely branded as money. Think of them as digital medallions that mimic the surface appearance of money while being bought and sold for dollars within the actual monetary system.

These digital medallions can be used for exchange via a process called countertrade. I can hand over two $500 wristwatches in payment for a $1000 computer, but implicitly I’m actually selling the watches to the owner of the computer for $1000, and then handing them that money back to buy the computer. An alien watching that interaction might believe that the watches are a type of money, but really the money is the dollar system hidden in the background. Similarly, I can countertrade fragments of dollar-priced Bitcoin for a dollar-priced computer, but the reason Bitcoin is effective here is because it parasites off of the dollar rather than challenging it.

To listen to the audio version read by author Brett Scott, download the Next Big Idea App today: