Ali Vitali is a Capitol Hill Correspondent for NBC News. She covered the 2016 and 2020 presidential contests from primary to inauguration—on the ground and with the candidates—as well as the 2018 and 2022 midterms, from across the country and in the nation’s capital.

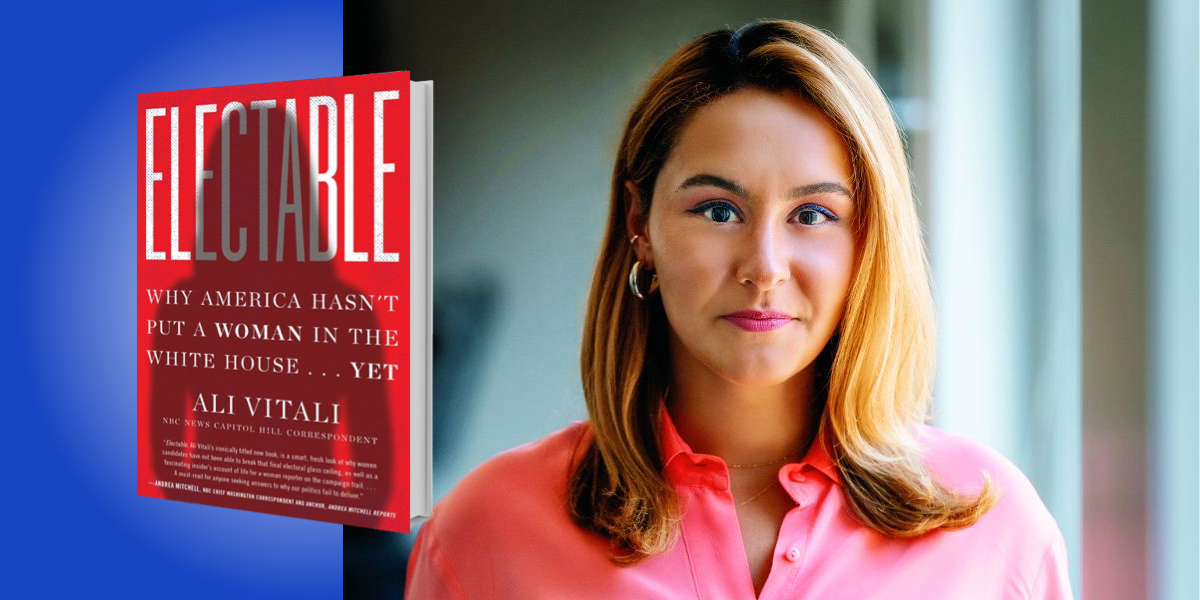

Below, Ali shares 5 key insights from her new book, Electable: Why America Hasn’t Put a Woman in the White House…Yet. Listen to the audio version—read by Ali herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Electability.

Everyone wants to back a candidate who can win, which is why electability is an important metric. Gender factors into how electability is assessed. Understanding biases and how they manifested in recent election cycles for female candidates is the first step towards disrupting those trends and leveling the playing field for candidates of both genders.

Can a woman win? was the key question of the Democratic primary at a pivotal moment, mere weeks before the Iowa Caucus in January 2020. Looming over the field was also a more specific question: Can a woman beat Donald Trump— especially after Hillary Clinton’s loss in the presidential election of 2016? Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren sparred over these questions on the pre-caucus debate stage after news broke that, during a private dinner in 2018, Sanders told Warren that he didn’t think a woman could win the presidential. This is according to Warren, though Sanders denied the account—which also thrust into focus the dynamics of believing men over women. But the larger issue was that unanswerable question: Could women do what had never been done—was it time a female could win the United States presidency?

“Understanding biases and how they manifested in recent election cycles for female candidates is the first step towards disrupting those trends and leveling the playing field for candidates of both genders.”

Flying from the Iowa Caucus to the New Hampshire primary, Warren was asked about how gendered dynamics affected her experience in Iowa, and what she hears from voters. She was candid with the dozen of us traveling reporters, sharing that, “Everyone comes up to me and says, ‘I would vote for you, if you had a penis.’”

2. Likeability.

Electability is bound to likeability—especially for women, for whom being liked impacts their ability to get votes, and thusly their ability to win.

It’s a metric that dogged Hillary Clinton her entire political life. Most of us recall the debate stage moment in 2008 when then-Senator Barack Obama quipped that Clinton was “likable enough” after the moderator asked her what she’d say to those concerned about “the likability issue.” Her likeability was a threat to her candidacy, despite voters agreeing that Clinton was the field’s most experienced and “electable” candidate. At the outset of her presidential run in 2016, The Washington Post revived the metric: “Regardless of whether it’s fair, it’s a question that has followed Clinton. And even if it’s a double standard, it’s still a potentially real factor for her when it comes to getting people to vote for her—at least theoretically.”

But it’s more than theoretical. A study by the Barbara Lee Family Foundation (BLFF) found that “voters will support a male candidate they do not like but who they think is qualified, but don’t apply the same standard to women.” It called to mind the dozens of voters I met who backed Trump even though they didn’t like his brash persona.

“Her likeability was a threat to her candidacy, despite voters agreeing that Clinton was the field’s most experienced and ‘electable’ candidate.”

If you’re trying to make sure everyone likes you, it can be hard to differentiate yourself from the field, or attack rivals—which is also part of being a candidate. This only complicates the situation for woman candidates further.

3. Proving qualifications.

That same BLFF study also found that for men, qualifications are assumed, whereas women have to prove their qualifications. It’s something that became a pivot point in the campaign conversation for Senator Amy Klobuchar and Pete Buttigieg (actively Secretary of Transportation for President Biden), after Klobuchar was quoted in the New York Times as effectively saying that a woman with equal or less experience than Buttigieg would struggle to be taken seriously as a presidential contender.

Some in Klobuchar’s orbit were reticent about engaging further. Being a woman who was also in the race for president, complaining about the unfair dynamics faced by women running for president could ring hollow or seem selfishly biased. But Klobuchar leaned in any way—not because she wanted to win because of her gender, but because she saw it as a fact that women had to do more to be taken seriously. This, of course, was and is true. I look back on this news cycle and wonder how anyone could have seen it any other way.

4. Assessments of Vice President Kamala Harris.

Kamala Harris is historic, glass ceiling breaking, and trailblazing. The first woman and woman of color to hold the role of Madame Vice President. It’s a milestone, but remains a difficult road.

“[People] are all struggling for the metrics to assess her because we expected that her ‘newness’ would manifest as tangibly different.”

Some say Harris is doing a good job but is getting a bad shake. Others say she falls short of expectations. To me, they are all struggling for the metrics to assess her because we expected that her “newness” would manifest as tangibly different. This is fundamentally unfair because, in theory, each new vice president is new. But also, this mentality set her up to fall short of expectations before she even began. There was no expectation for Pence or Cheney or Gore to reshape the office. Why, suddenly, is there anxious foot-tapping for Harris to do so? This is inextricably linked with her identity—for better and for worse.

5. How this history happens.

I don’t know who the first female president will be, though I have some ideas. Multiple experts and former candidates (including Hillary Clinton) have shared their own speculations on who will become the first female president. Despite Democrats being leaders in putting viable women into the candidate pipeline, the first woman president could very well be a conservative. This is how it has happened in other countries that have beaten us to this milestone.

I expect that the upcoming 2024 election cycle will be very female—despite still being dominated by men. Specifically, dominated by Joe Biden and Donald Trump because both say they’re going to run for president again. There will likely be women running from both parties, with more than one in each field. I hope it becomes the norm for presidential election cycles, where there are multiple female candidates rather than one singular woman. I hope that they’ll run on a more level playing field than the one on which women who came before them contended.

To listen to the audio version read by author Ali Vitali, download the Next Big Idea App today: