Below, Cory Doctorow shares five key insights from his new book, Enshittification: Why Everything Suddenly Got Worse and What to Do About It.

Cory is a science fiction author, activist, and journalist. His many books include the sci-fi novel The Lost Cause, about hope amidst the climate emergency, and the nonfiction title The Internet Con: How to Seize the Means of Computation, which serves as a disassembly manual for Big Tech. In 2020, he was inducted into the Canadian Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame.

What’s the big idea?

The digital platforms we have come to depend on for so much have gone from bad to worse. Everything online is becoming enshittified. The answer to what we must do to clean up this mess can be found in how we got here.

1. The natural progression of enshittification.

There are observable phenomena that we can see from outside a platform as it goes bad. This follows a classic three stage process:

- Stage One: the platform is good to its end users. It has the capital to deliver a high-quality service. For instance, back when your Facebook feed only displayed friends’ posts.

- Stage Two: the platform takes back some of the value that it was giving its end users and gives it to a group of business customers. Like when Facebook started spying on users and putting things in their feeds that they’d never asked to see.

- Stage Three: all available surplus is taken away from the business customers and the end users. Publishers must pay to boost their content just so their subscribers can see it, and no one sees their stuff unless they post whole articles, with no link to their own website.

Users stick around during Stage Two because they are locked in. There are lots of different ways that tech platforms can lock users in. In the case of Facebook, it’s something economists call the collective action problem. You’re there because your friends are there, and your friends are there because you are there. In come publishers, and they get stuck there too because they are reliant on you, who has been taken hostage by your friends.

In Stage Three, publishers become commodity suppliers to, in our example, Facebook. Advertisers pay more for ads, but they have lower ad fidelity and gigantic amounts of ad fraud. And you, well, your feed has dwindled to a kind of homeopathic residue of things that you actually asked to see. That’s the three-stage process by which platforms decay.

2. The mechanism by which platforms decay.

When digital businesses go wrong, they can go wrong in a special way. Digital businesses can change the rules on a per user, per session basis. They can change prices, recommendations, and every aspect of navigating their service based on inferences made from their surveillance data about you. I call this twiddling.

There is a company called Plexure, which McDonald’s holds an investment stake in, that advertises its ability to use surveillance data to figure out how to raise the price of your go-to breakfast sandwich. For instance, it can determine that you will be less price sensitive when you order in the McDonald’s app on the day you get paid.

“Digital businesses can change the rules on a per user, per session basis.”

There are also apps used by hospitals to hire in contract nurses, like ShiftMed and CareRev. These apps buy nurses’ credit bureau data. If a nurse carries a high degree of debt, then it offers them lower wages for their shift.

These are the kinds of scams that many merchants would have happily pursued in the past, had they not been so labor-intensive. Digitization allows the rules to change from moment to moment, second to second, and user to user.

3. Constraints that, historically, stopped enshittification.

We have had digital platforms for a long time, and it used to be that either they were good and remained, or they went bad and disappeared. What stopped platforms from enshittifying before they all enshittified?

- They had competition. But that ended because we let companies, like Facebook, buy their competitors, like Instagram.

- They faced regulations. Fines or penalties for cheating users outweighed possible gains from bad behavior.

- They had a powerful workforce. Historically, tech workers liked fighting for the user. They could quit their job and get another across the street on the same day, so they were able to tell their bosses ‘Go to hell’ if ordered to enshittify things.

And finally, there is a technical idea called interoperability. There’s always a computer program you can write that undoes someone else’s mischief. If HP sells you a printer programmed to make sure you don’t use generic ink, then you can just disable that program by running another program that overrides it. For every 10-foot pile of shit a platform builds, there’s an 11-foot software ladder you can build to go over it. But we stopped enforcing the things that stop platforms from enshittifiying—and so here we are.

4. Permission to enshittify.

What changed to allow for enshittification? First, we stopped enforcing antitrust law. We allowed companies to buy their direct rivals. We permitted predatory pricing: Uber sold taxi rides below cost, losing 41 cents on every dollar to the tune of $31 billion for 13 years until all its competitors had exited the market. And exclusivity deals went unchecked, along with all kinds of other things prohibited under antitrust law. This started in the 1980s, but it really got going with the tech sector in the 2000s.

When you lose that competition, you also lose regulation. When there are a hundred companies in a sector, they can’t easily capture regulators or coordinate to bend the rules in their favor. But when there are only five, four, three, two, or just one company—as is the case in many sectors of our economy—capturing regulators becomes much easier. We haven’t had a new privacy law since 1988, when Ronald Reagan banned video store clerks from telling newspapers which VHS tapes you rented. Congress hasn’t enacted significant protections against technological privacy threats since Die Hard was in theaters. Why? Because there’s so much money to be made by violating your privacy, and that money shapes policy.

We also had a powerful tech workforce, but they lost that power because they never used it to unionize. Once the supply of workers outpaced demand, the tech layoffs were devastating: half a million in the U.S. in the last three years. Suddenly, tech workers didn’t have much leverage.

“Our policies allowed companies to act worse and worse without facing consequences.”

And finally, with the growth of IP law, the interoperability that allowed you to install ad blockers, use third-party tools, or record content off of apps—all of that went away. IP law made it illegal. We lost the constraints that had prevented tech bosses from abusing users. Our policies allowed companies to act worse and worse without facing consequences, so the obvious solution is to bring back those policies that held them accountable.

5. Unions need to make a comeback.

We need to revive unionization and union law. President Trump has eradicated union law in all but name, but just because you get rid of the rules doesn’t mean the game is going to end. Looking back at history, we didn’t have union law that then led to the formation of unions. We had illegal unions that won union law. Trump has torn up the rule book, meaning there are no rules stopping unions from playing hardball—and they have to.

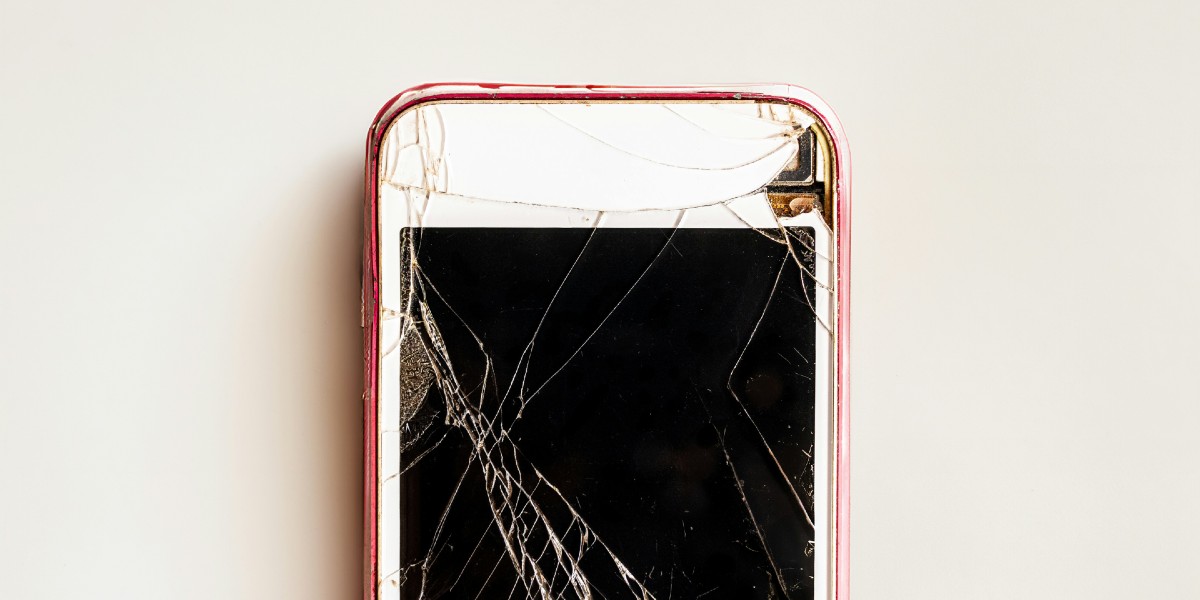

Every worker is an ally here. The way that tech bosses treat their worst-off workers—Amazon drivers or Chinese factory workers making iPhones—is how they would treat their programmers if they could. And these days, they can.

We also need to revitalize antitrust law. Fortunately, this has begun. We’ve seen a worldwide resurgence of antitrust law over the past four years. Trump has scaled it back, but antitrust law is being revitalized in the European Union, Canada, Australia, Germany, Spain, France, South Korea, Japan, and China.

Then there’s the issue of restoring regulation. We need rules that allow people to defend themselves from tech. We need to change how IP law works, and we need rules that stop tech from preying on users. We need privacy laws, too.

On the privacy front, people from all sides of the political spectrum are angry, but don’t realize that the different things upsetting them all trace back to the same problem: their personal information being misused. Some worry that Instagram is brainwashing their kids, or Facebook is radicalizing grandparents into QAnon, and so on. The mistake is seeing these specific issues as separate problems. All these people care about privacy, even if they don’t recognize it as such. That shared concern can be the start of a coalition that could actually make a difference.

Enjoy our full library of Book Bites—read by the authors!—in the Next Big Idea App: