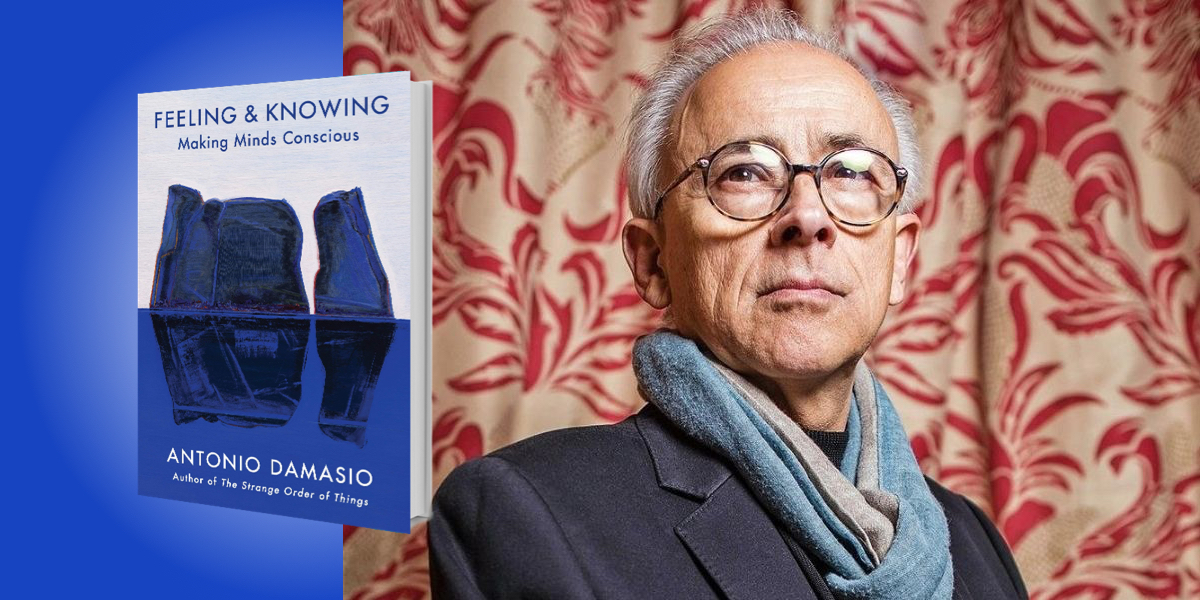

Where do our feelings come from, and how do they shape decision-making? These questions have animated Antonio Damasio’s illustrious career in neuroscience, and inspired his bestselling books, Descartes’ Error and The Strange Order of Things among them. Damasio, who directs the USC Brain and Creativity Institute, lives in Southern California with his wife, Hanna.

Below, Antonio shares 4 key insights from his new book, Feeling & Knowing: Making Minds Conscious. Listen to the audio version—read by Antonio himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. The contents of feelings always correspond to states of the body.

The variety of our feelings is quite wide. Feelings can convey pain, hunger, or thirst; well-being or malaise; desire or compassion; sadness or joy. But the insight here is that the contents of feelings always correspond to states of the body. Whatever the message is that feelings deliver in our minds, that message always describes, in mental terms, a specific state that is now unfolding in our bodies, within our all-too-mortal flesh.

Whether you are in pain, thirsty, joyful, sad, or in a meditative mood, your body adopts a particular physical and chemical profile. Feelings correspond to that profile. Feelings are the descriptions of changes that happen in our internal organs or in the thick of our skin, under the influence of particular chemical molecules.

How are those “descriptions” fabricated? First, the myriad nerve endings placed in every nook and cranny of our bodies deliver to the brain a particular configuration of signals corresponding to the body at that moment.

Second, the brain uses those signals to assemble three-dimensional maps, which result in mental images related to the state of the body.

A third and amazing fact is that on the basis of the images that the brain makes of its own body, the brain talks back to the body. This talking back has a purpose. In case the life process is veering off course, the talking back helps adjust the body state and regain a “homeostatic” range—that is, the range compatible with survival and, preferably, well-being.

“Feelings are the descriptions of changes that happen in our internal organs or in the thick of our skin, under the influence of particular chemical molecules.”

Another curious fact: Nothing comparable happens with the maps and images that our eyes and ears collect from the external world. Dealing with the body is a special business.

Traditionally, feelings were believed to be something ethereal, as difficult to pin down as smoke in the air. But nothing could be further from the truth. Feelings are firmly planted in our nervous systems, where they describe—quite graphically, with the help of three-dimensional maps—the state of life within our bodies.

2. The notion that body and brain are separate is false.

How do we reach this insight? By considering the architecture of the nervous system and seeing how it relates to the rest of the body.

Both the nervous system and the rest of the body are made of living cells. Those living cells form tissues, the tissues form organs and, subsequently, the organs form systems. To be sure, nervous cells, which are known as “neurons,” are very special cells, uniquely recognizable by their shapes and operation. But the cells in the heart, lungs, and kidneys are also special and unique. The smooth muscle cells that move our guts are special too—and they are quite different from the muscle cells that power our biceps, deltoids, and quads. So the idea that brain and body would be separate because the cells in the brain are special does not really hold. But the myth of the separation of body and brain really falls apart when we consider the two following facts.

First, neurons can go everywhere in the body and bring information back to the central nervous system.

Second, as I mentioned earlier, the central nervous system has a chance to talk back to the body parts that messaged it and, by doing so, to influence the body in return. The central and peripheral components of the nervous system are fully integrated with each other, and, just as importantly, with the rest of the body—i.e. all of our internal organs plus the skin, blood vessels, and musculature. Sadly, this extraordinary integration continues not to be recognized in most conversations about mind and brain, and is simply ignored in relation to consciousness.

“The central and peripheral components of the nervous system are fully integrated with each other, and, just as importantly, with the rest of the body.”

It’s important to note that the nerve cells in charge of gathering information from the world outside of our bodies (“exteroception”)—achieved through vision, hearing, touch, smell, and taste—are quite different from those nerve cells dedicated to internal information-gathering (“interoception”). Nerve cells for exteroception are quite modern and sophisticated, and they resemble well-insulated electric cables. The cables are called “axons,” and the insulation is called “myelin.” Myelin insulation keeps the messages pure, which is important if you want to preserve the fidelity of signals and create accurate representations.

Neurons that are concerned with the interior of our organisms, however, are not well-insulated, and many of them lack myelin. There are other differences, too, but this one, on its own, is an extraordinary revelation. It tells us that the conversation that goes on between body and brain is facilitated by a lack of barriers. Accordingly, the nerve cells on which feelings depend are well integrated with non-nervous elements of our body. They form a rich, commingled partnership, working together.

3. Feelings are spontaneously conscious.

Feelings are the actual beginnings of consciousness in the long history of life, certainly the initiators of consciousness in the evolution of vertebrates like us. Feelings would be of no use to us if they were not conscious. When you feel thirsty, you are conscious of that fact. Feeling thirst informs you that the water balance in your organism is off, and that knowledge is essential for you to do the next smart thing, which is to drink. The same happens when you have pain. When you have a toothache, you are certainly conscious of that fact—you are being told by your brain that there is a problem in your body, and that you should investigate it.

Our body can be in a state of good regulation and good harmony, or can be lacking in some particular nutrient or water, can be too hot or too cold, or can be in the middle of an infection. Feelings are a major help with the maintenance of homeostasis, the state of harmony of body functions that is required for survival.

“Thanks to feeling—which really means, thanks to consciousness—we have a say in our destiny.”

But instead of simply relying on the automatic regulation of life processes, we can take the advice of feelings. Feelings tell us, in no uncertain terms, that the body is either in the homeostatic range, the one compatible with the continuation of life, or is deficient in some way. This is a big development in the history of evolution. Creatures without nervous systems—or with simple nervous systems—regulate their life intelligently, but in an automatic, non-conscious way. They do not think. Creatures with elaborate nervous systems like us enjoy the privilege of another mechanism of life regulation. Thanks to feeling—which really means, thanks to consciousness—we have a say in our destiny.

Now, you might ask about feelings of well-being, or feelings of desire. How does the knowledge of those very conscious feelings help us with our lives? Are they a useless luxury?

Well, they are not. They also provide important knowledge. Feeling well gives you freedom to pursue activities that have little or nothing to do with curating life in your body. Combined with skills and curiosity, well-being allows you to be creative in art, or business, or even in science, in case all else fails. As for desire, it may well help you find a mate and maintain the species!

4. The people, actions, and thoughts that flow along in our minds affect us.

As we go about our daily lives, a continuous stream of images in our minds describes the people we meet, the things we do, and the thoughts we think. What does that mean?

First, it means that the images inevitably and frequently cause some sort of emotion, weak or strong, pleasant or not. Second, all of those emotions change the state of the body and become emotional feelings. Now, the beauty of those emotional feelings is that they describe the interior of an organism changed by its own thinking. They naturally reveal to the mind of that organism that it belongs to the body where the feelings come from. This is really a circus act—the belonging together allows each mind to locate the knowledge conveyed by feelings within its unique body. That is the trick that reveals ownership and turns knowledge into experience, the trick that renders the knowledge “conscious” in the true sense of the term.

In the end, the kind of consciousness that feelings help generate is the only kind of consciousness we need. It does its job for anything we see, hear, or touch, because the “natural” ownership of mind can only be established by the feeling process.

To listen to the audio version read by author Antonio Damasio, download the Next Big Idea App today: