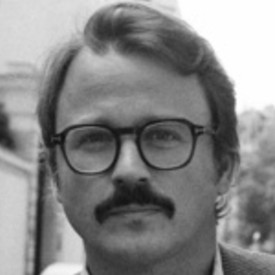

Simon Critchley is the Hans Jonas Professor of Philosophy at the New School for Social Research in New York and a Director of the Onassis Foundation. He has written over twenty books on topics ranging from philosophy, the arts, sports, and mental health.

What’s the big idea?

Mysticism is an ancient practice that is largely unacknowledged in contemporary life but maintains universal accessibility and importance. We engage with vestiges of mysticism, often unaware that we are connecting to a tradition that holds the power to save us from ourselves. Intentional engagement with modern mysticism clears a path away from doubt and toward love.

Below, Simon shares five key insights from his new book, Mysticism. Listen to the audio version—read by Simon himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. We need relief.

With mysticism, we’re offered a path: an itinerary from woe to well, from things being ill to things being better. We can be lifted from woe, pain, melancholy, and doubt into the sense of being saved. With mysticism, being saved means being saved from ourselves—from the hell that each of us carries within. We can push ourselves aside. I don’t believe that there is a place called hell where souls burn for eternity in damnation. But I do think the idea that we are hell, that we carry that pain and suffering within us, makes sense. To be saved is to push that self aside, to push that ego aside, and open to something else. This pushing aside opens the experience of ecstasy—ecstasy as being liberated from our subjectivity, from the curse of reflection. This can lead to a released existence where we can enter a detached, flowing openness between us and the world. With that detached openness, we can experience being in the world and being with others without division, without hatred, and without a lofty sense of moral superiority; there is no splitting between us and that which is.

We need relief from the misery, the anxiety, and the feelings of meaninglessness that pervade life. My book asks us to push ourselves aside and open up to the experiences of love, passion, and aliveness that exceed the self. It’s a question of embracing mysticism as a way to experience life more intensely. One way to define mysticism is to recover the intensity of existence and escape the heaviness and doubt of existence.

The book begins with a discussion of Hamlet as the great dowser, the cleverest person we can imagine being in a room with. This extraordinary intelligence that we find in Hamlet, the ability to soliloquize on any topic and to doubt everything and everyone, leads to the extinction of the capacity for love—his love for Ophelia and his love for the world. We need a way of escaping doubt because the opposite of doubt is not certainty, it’s love.

2. What is mysticism?

Mysticism cannot be reduced to a theoretical belief in the existence or nonexistence of a deity or some transcendent being. Rather, mysticism is a set of practices that free us from our usual habits and allow us to stand ecstatically with what is. So, mysticism is an eminently practical activity. The practices of mysticism go back to the Middle Ages: reading, meditation, prayer, composition, and contemplation. Everything here begins with reading.

“Mysticism is an eminently practical activity.”

Mysticism seeks to describe a countermovement from doubt to delight, from dereliction to ecstasy. It aspires to use words and sounds to lift us out of misery and enable a transfiguration of self and world. This is very difficult to explain and very simple to do. The ultimate goal is a released existence where thinking is freed from the tyranny of the will. At the core of Mysticism is an idea of freedom that would not be freedom of the will, but freedom from the will. That’s what released existence means—released into openness.

3. Are we still mystics?

You might say, well, this is all fine if you’re a medieval Christian or a Zen monk or something, but what about me? What about us? Practical mysticism lives on in aesthetic experience, in the experience of art, especially in music.

Listening to the music we love animates the world and allows the world to burst with sense and feeling. It’s a very mysterious thing, listening to and loving music, but it’s something we do in a very ordinary, everyday, practical way. Music holds us in an emotion and allows access to something larger than the self, what I call sensate ecstasy.

I think we are still mystics when we listen to music. I don’t think it’s possible to be an atheist when listening to the music that you truly love, the songs that opened the world for you. We are still mystics. We’re also mystics when we go to sleep and dream.

4. What mysticism can do.

Mysticism allows us to step back from the world that overwhelms us—with its endless noise, notifications, updates, and news flashes—by using the power of imagination. Mysticism combats the world with empathy and kindness. Kindness is a key concept regarding the book’s heroine, Julian of Norwich, who wrote in the late 14th or early 15th century. She was the first woman to write a book in English. At the core of her radical theology is kindness, meaning that we are of the same kind. We are kin, and kindness resolves all conflicts.

Mysticism also allows us to revive what is archaic and see our experiences and current crises in the huge context of the whole sweep of the human endeavor. We are modern people, we are skeptics, we engage in critique, and so on and so forth. Mysticism allows us to revive something old about us that we keep within ourselves. It’s still there. We must learn to access it.

“Mysticism combats the world with empathy and kindness.”

For as long as there have been hominids of any kind, there has been religion and mysticism. Mysticism can give a very different sense of the environment we inhabit. It has an environmental implication, an environment that is less anthropocentric and more capacious and full of life—human life, animal life, plant life, the life of things, and divine life. For a mystic, everything has agency, everything is alive.

5. Why is mysticism important?

A religious sensibility is perhaps the most shared thing on the planet, and this sensibility makes no distinction between rich and poor, educated and uneducated, or the haves and have-nots. My book is a rebellion against secular elitism, a kind of atheistic elitism, and an attempt to take the many mystical experiences had by millions of ordinary people seriously, to take religion seriously and not see it as something embarrassing or belonging to the past.

Mysticism also allows us to cultivate practices of radical attention, and we’re in desperate need of such practices. As T. S. Eliot said, we are distracted from distraction by distraction. We need to attend. The main form of attending that the book performs is reading. Through disciplined close reading, we can push ourselves aside and push aside whatever stale and dull monologue is running through our heads and open ourselves to that which is and that which is outside and beyond the self. So, the book is also a call for practices of radical attention. In particular, the attention of close reading, what the mystics call lectio divina, meaning divine or inspired reading through the prayerful study of scripture.

If you’re not a reader of books or books don’t do it for you, we can do the same thing in other ways with listening, hearing, or seeing. We need attention that is outside and beyond the self and an attentive discipline that can save us from the slough of despond in which we often wallow. We can push ourselves aside and find some resonance in the clear middle distance of transcendence. That’s all the mysticism we need, and it costs nothing.

To listen to the audio version read by author Simon Critchley, download the Next Big Idea App today: