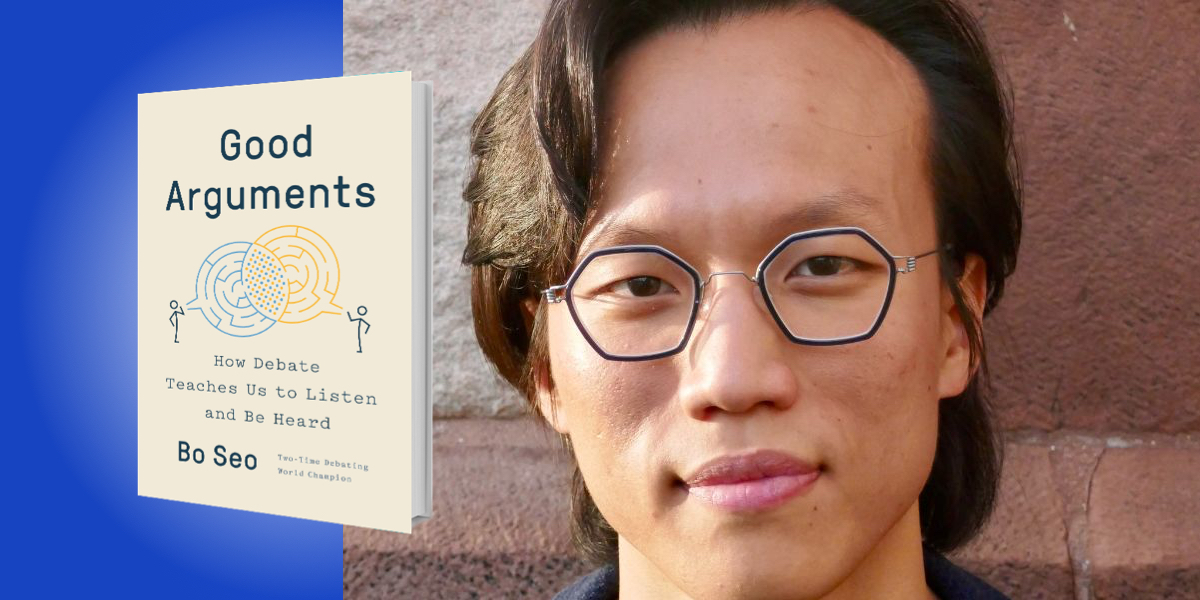

Bo Seo is a two-time world debate champion and former coach of the Australian national debating team and the Harvard College Debating Union. Below, he shares 5 key insights from his new book, Good Arguments: How Debate Teaches Us to Listen and Be Heard. Listen to the audio version—read by Bo himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Debate can unleash your voice.

When I moved as an eight-year-old from South Korea to Australia, I didn’t speak English. I quickly learned that the hardest part of crossing language lines was adjusting to real-life conversation, and the hardest conversations to adjust to were disagreements. That was where passions ran high, ordinary rhythms of speech broke down, and people started to interrupt.

I sensed that my differences from my peers, if exposed, could mark me as an outsider and let slip whatever foothold of belonging I had achieved in this new place. That made me resolve to be very agreeable, to smile, to nod, and to keep most of my thoughts to myself. What broke me out of that posture of conflict aversion was a promise from my fifth-grade teacher that in debate, when one person speaks, no one else does. To someone used to being spoken over and spun out of conversation, that sounded like a kind of salvation.

On the debate team, I found a structure, community, and body of knowledge that allowed me to raise my voice and be heard.

“To someone used to being spoken over and spun out of conversation, that sounded like a kind of salvation.”

2. Every argument must establish a claim’s truth and importance.

An argument is not a random grab bag of thoughts or exclamations. It’s not a repetition of all the things you think about a particular subject. An argument is a tool for changing minds, and it has two basic burdens of proof. First, showing that its main claim is true, and second, that this claim is important.

Imagine arguing that we should stop eating meat because vegetarianism benefits the environment. For that argument to succeed, first you have to show that being vegetarian is, in fact, good for the environment. Otherwise you have no legs to stand on for the claim that healing the environment means no longer eating meat. Second, the true question at the core of this argument asks, why should we privilege the health of the environment over personal enjoyment?

It’s often that second part that people neglect. It’s not enough to show that you have a point—you have to make it count for the other side. That involves asking why the truth of this argument should change your mind and behavior.

“It’s not enough to show that you have a point—you have to make it count for the other side.”

3. Choose your battles, and win.

When you start picking up the strategies and secrets of good debate, every objectionable thing people say seems like an opportunity to quarrel and make a point. To the one holding the hammer, everything seems like a nail. But we know that good conversations and relationships have agreement alongside disagreement. If one measure of cleverness is the ability to argue well and make a point, then wisdom rests in knowing when to argue and when to stop. I got around this problem by developing the RISA Checklist.

RISA: Is the disagreement Real, Important, Specific, and Aligned? Before entering into a disagreement, for example, ask yourself if this is a real disagreement as opposed to an imagined slight, or something like that. Second, is the disagreement important enough to justify arguing? Third, is the disagreement specific enough that you can make progress within the allotted time? And fourth, are the two sides aligned in their objectives for the dispute? For instance, is the other side just looking to hurt your feelings?

Meeting the RISA Checklist doesn’t guarantee that an argument will go well, but it suggests that there are conditions such that the argument could go well. By being deliberate and not jumping into disagreements out of pride or defensiveness, we can focus on disagreements that are most likely to be productive.

“Is the disagreement Real, Important, Specific, and Aligned?”

4. Empathy can arise from action.

As a kid, I used to hate being told to empathize with my classmates because I didn’t know what “empathy” meant. Some described it as a magical, mental connection that spontaneously arises when you look into the eyes of another person. Others described it as a virtue that the best of us possess and the rest of us can hope to find. In debate, I learned a different way of understanding empathy: empathy as a series of actions.

Much of debating is an exercise in certainty. You fully inhabit your perspective and come up with the best possible arguments for your side, recruiting the most persuasive evidence for your case. But in the last five minutes before the start of a round, the best debaters do something extraordinary. They turn to a new sheet of paper and come up with the four best arguments for the other side, or they look over their speech through the eyes of an opponent and try to find as many problems as they can.

Those are known as “side-switch exercises.” They don’t help you achieve empathy, exactly, because there is no substitute for really hearing where the other side is coming from. But it does create wriggle room. It gives you the sense that there may be another way of viewing this issue. At a time when many of our disagreements feel like trench warfare, with each side frozen in their position, unable to fathom where the other side is coming from, I think that wriggle room can help. It creates a space through which empathy might be able to arise.

“In debate, I learned a different way of understanding empathy: empathy as a series of actions.”

5. The opposite of bad disagreement is not agreement.

The opposite of bad disagreement is good disagreement. For most of history, entire groups of people were barred from speaking by virtue of their station in life. Multitudes lacked any platform or capacity to be heard. What we’re doing today—embracing diversity in our communities, giving people platforms to raise their voices in the public square, and trying to manage our arguments—all feels unprecedented. So I see the project of good arguments as utopian writing towards the future, the full outlines of which we cannot yet see at present.

We must regain confidence and faith in what good arguments can be, realizing that disagreement can be the basis of richer conversations, intimate connections, and more searching inquiries than mere agreement can ever hope to achieve. We must see argument as a skill, as an art form, as labor—not something we simply stumble into. The debate world acts as a symbol for what a community built around—not despite—disagreement can be, and harbors knowledge that we can apply in our day-to-day lives to start realizing that future. A future based not around agreeableness, but on good disagreement, which accounts for the richness of our differences and allows us to talk about them.

To listen to the audio version read by author Bo Seo, download the Next Big Idea App today: