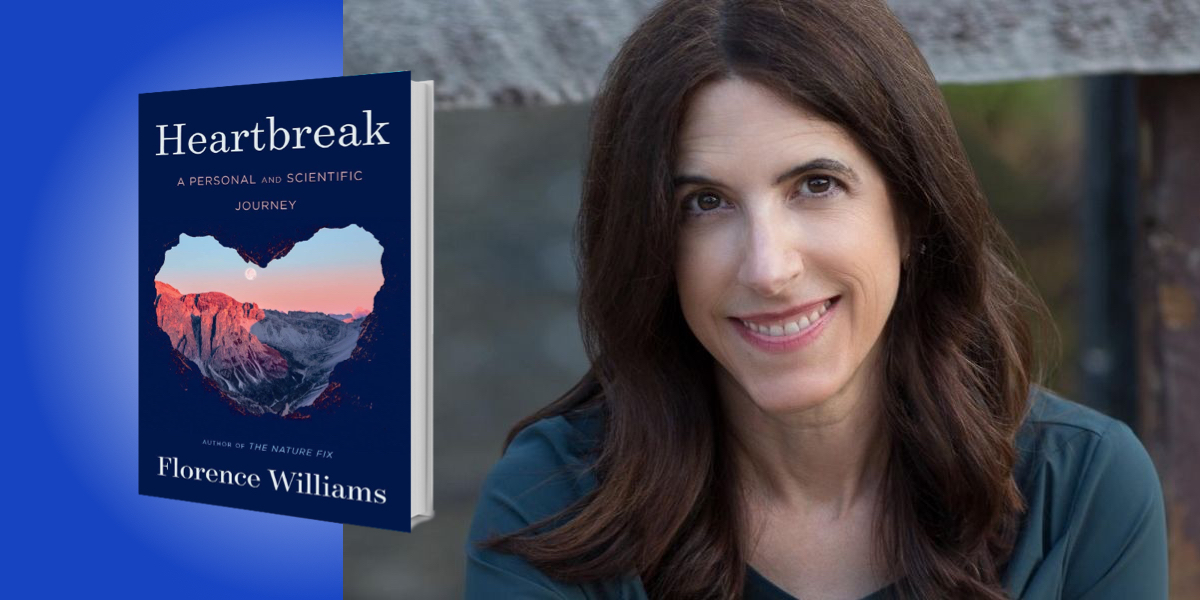

Florence Williams is a journalist, author, and podcaster. She is contributing editor at Outside magazine and a freelance writer for the New York Times, National Geographic, and Mother Jones, among others. Her work focuses on environment, health, and science.

Below, Florence shares 5 key insights from her new book, Heartbreak: A Personal and Scientific Journey. Listen to the audio version—read by Florence herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Take your heartbreak seriously.

It can be more hazardous to your health than you think. We tend to think of heartbreak as a metaphor, but in fact, people can have a literal heartbreak—it’s called “Takotsubo cardiomyopathy.” It happens after a big emotional blow. We hear sometimes of husbands and wives dying within a few days of each other, and that’s probably what’s going on. We have so many stress hormones flooding our heart that the left ventricle balloons out and is unable to pump.

There are other ways big emotional losses can affect our health. For example, if we’re feeling rejected in love, our body registers it in the same way as if we’d been abandoned in the jungle. So, our immune systems react. Our genetic transcription factors change to up-regulate cells for inflammation—that’s to prepare for a wound injury. At the same time, we down-regulate our genes for things like fighting viruses—not something that will serve us very well when stumbling through the jungle.

If you’re heartbroken or you know someone who is, you need to do what you can to calm your nervous system and get to the other side. For instance, do some of the things you love, some of the things that help you breathe. Maybe it’s going in nature, dancing, or hanging out with friends. Whatever it is, don’t try to suppress your emotions. Try to sit with them, feel them, let them wash over you. In this way, you can begin the long journey to healing.

There’s an urgency to recover from heartbreak because people who feel heartbroken and lonely (especially if it goes on for a while) are 23 percent more likely to face early death. They’re nine to 25 percent more likely to have cardiovascular disease, and their risk of metastatic cancer, metabolic disease, and dementia all go up. We can even lose IQ points if it goes on long enough.

2. Find authentic connection to friends, family, community, and the natural world.

It’s only by being vulnerable about our suffering that we can help other people become vulnerable with us in return. When that happens, we feel less alone. We can become more empathetic to other peoples’ suffering, even in the midst of our own. This, ultimately, can help open our hearts once it’s all over.

“It’s only by being vulnerable about our suffering that we can help other people become vulnerable with us in return.”

Be honest and open about your own flaws and failings, too. Other people will share theirs as well. Heartbreak can feel like such a singular event; sometimes we feel like we’re going through it alone because we don’t have close friends going through it at the same time. Some of us will only experience a heartbreak once or twice in a lifetime, so it makes sense that when you’re going through yours, you may not be in great company.

It might be tempting to crawl under a pile of blankets and shut the world out. It’s okay to do that occasionally for small amounts of time, but make the effort to get out from underneath that pile. It’s worth it.

3. Seek beauty.

Early in my reporting journey, I talked to psychologist Paula Williams at the University of Utah. She said, “Divorce is a big problem for people’s future health outcomes. We know they can die younger. We know they have increased risk of disease.”

But it seems like there’s one personality trait in particular that helps people become resilient and sail through these difficult events, and she said that personality trait is openness. It’s the people who are able to cultivate and connect with beauty, who are able to feel goosebumps when, for example, they’re hearing a symphony or looking at a waterfall. It’s the people who are prone to experiencing awe who can make meaning from their stories. These people connect distant parts of their brains with the frontal cortex that monitors self-concept. They’re able to keep their sensory brains alive and feel connected to something larger than themselves.

When we experience awe, it gives us perspective. It temporarily shuts down the cognitive part of our brain because we’re trying to understand this amazing beauty in front of us. Sometimes we will draw a picture of ourselves smaller in the landscape when we’re looking at something like Yosemite, compared to when we’re looking at a streetscape. I think we can all relate to this when we’re looking up at a starry sky and feel like a small speck in the universe. This humility, this loss of ego, is incredibly important for mental health. It gives us perspective, helps us feel connected to the world, and it stills our mind long enough to understand what’s going on.

“It’s the people who are prone to experiencing awe who can make meaning from their stories.”

This window of learning may translate to learning about our place in the world, which is possibly why corporate events take place in beautiful places, or religious ceremonies take place in magnificent cathedrals. These are the times when we feel most connected to other people and are most open to ideas. We can use it as a moment to consider who we want to be as we move forward from difficult junctures in our lives.

4. Create ritual.

Heartbreak only happens once or twice in our lifetimes. It’s not something we’re used to ritualizing—it’s not like a funeral, and certainly not like a wedding. And yet, if we can find some way to mark this passage in our life, maybe to look forward to the next chapters and find connections with other people in the process, then we can feel that it’s a normal part of being human. We can start to create meaning from it.

When we can create a ritual, it helps us feel that we’re exerting control over events that we don’t feel control over. I, for example, sent my wedding ring in a lettuce boat down the Potomac River to reach the Atlantic Ocean. I was able to do that with friends and, by sharing that experience, it also triggered a sense of awe.

Throughout time, cultures have ritualized transitions, such as adolescence marking entrance into adulthood. Why not take an event like a heartbreak and mark it as a transition into a different, not necessarily worse, part of your life?

I visited the Museum of Broken Relationships in Zagreb, Croatia. It’s filled with objects that the heartbroken have sent in as a way to commemorate and ritualize the relationships that they’ve lost. These objects are placed under glass and bright lights. The people who send them also write a paragraph or two explaining the object. Dozens of people walk through this museum understanding that loss is a universal experience, and one that can even have humor. Some of these objects were things like a water bottle that a boy gave to a girl on a beach in the Mediterranean. There was even an exercise bike that someone sent in because they’d found their wife’s lover on this bicycle. There was a lot of melodrama, but also moments of humor.

“Why not take an event like a heartbreak and mark it as a transition into a different, not necessarily worse, part of your life?”

Storytelling is a great way to make sense of your experience. If you tell a story in a paragraph or two, there’s a beginning, a middle, and an end. It’s a pathway to find some closure.

5. Find purpose by finding meaning.

Sometimes it’s trickier to find our purpose moving forward. But a big question to ask is not what happened to me?, but rather what did I learn? How can I use the lessons from this difficult experience to become a better person, and also help others through their suffering?

One of the great ironies of heartbreak is that the scars in your heart can help open it up. That’s because we become a little bit more comfortable with big emotions. We understand that as we’re feeling more pain, perhaps we’re also feeling more joy. Ultimately, I found that by riding these extremes of emotion I felt more alive, even when that meant feeling pain.

When we feel more compassionate toward the pain and suffering of others, we show up for them better. We show up for the people we love, become better listeners, and more empathetic. We may even grow more concerned for people we don’t love, strangers in our communities, as we grow less consumed by merely our own problems.

Heartbreak can be one of the most transformative passages in our lives. When we learn to become more open to the real, authentic emotions of other people, more connected to the natural world, better able to see beauty and seek awe—those are the things that make us feel our humanity, our togetherness, and our purpose in this wide, beautiful cosmos.

To listen to the audio version read by author Florence Williams, download the Next Big Idea App today: