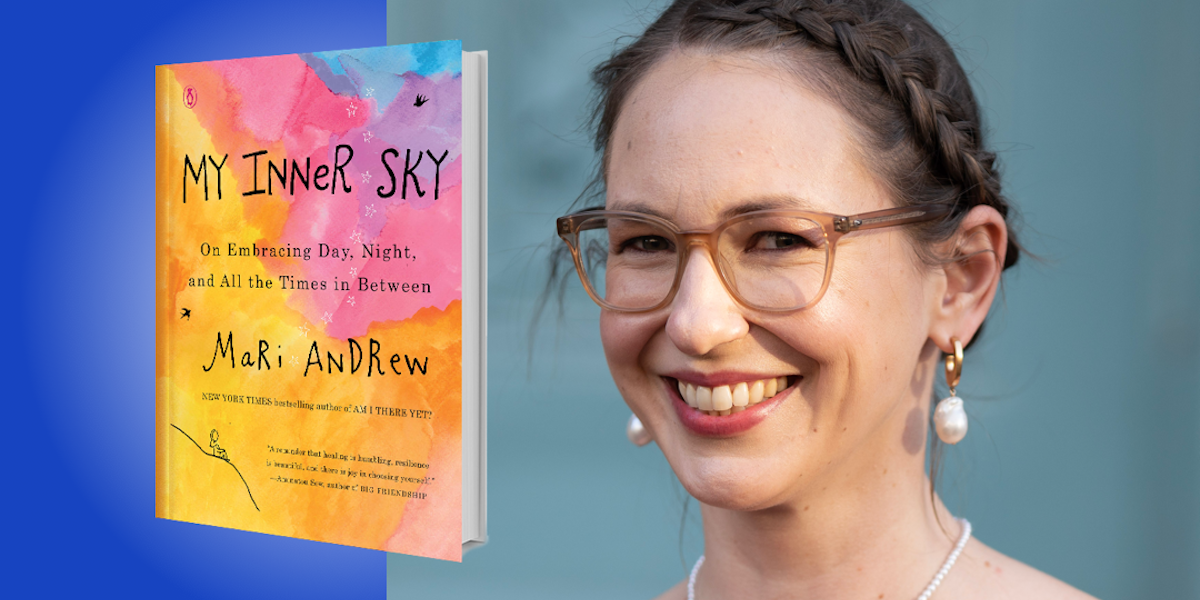

Mari Andrew is a writer, artist, and speaker based in New York City. Below, she shares 5 key insights from her new book, My Inner Sky: On Embracing Day, Night, and All the Times in Between (available now from Amazon). Listen to the audio version—read by Mari herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Present thinking over positive thinking.

I started writing My Inner Sky, a collection of personal essays about in-between and transitional times, when I was recovering from Guillain-Barre Syndrome. GBS is an autoimmune disease that temporarily paralyzed almost my entire body while I was living abroad. I spent a month in the hospital, and the recovery time took almost two years. In many ways, it was emotionally easier to be sick than in recovery—no one knew quite what to do with my recovering self. Society isn’t set up for the transition times. We over-value beginnings, ends, binaries, and distinctions—like the difference between sickness and health.

At the time, the idea of positive thinking was in the zeitgeist. I constantly saw slogans: good vibes only, choose happiness, make it an amazing day. But while I was in recovery from serious illness, I was frustrated, lonely, and longing to be back to normal, not knowing when or how that would be. I couldn’t really think positive, because that would be lying to myself. I was scared, and sometimes cynical, and other times hopeful, but not happy.

“Present thinking brought beauty and goodness into my life, whereas positive thinking just made me feel like I was choosing the wrong emotional state.”

In order to stay resilient, I had to be really present to how I was feeling—and not try to rush the dawn when I was still in the night. When I committed to self-honesty and explored all my feelings, I felt acceptance, relief, and even renewal. Present thinking brought beauty and goodness into my life, whereas positive thinking just made me feel like I was choosing the wrong emotional state. Being present, rather than positive, is what ultimately helped me heal.

2. All emotions belong.

Our society has presented us with very rigid, binary ways of thinking about emotions: that happiness is the opposite of sadness, that feelings come one at a time, and that gratitude is the antidote to suffering. I believe that every feeling is worth paying attention to. If we give our attention to all emotions—even, perhaps especially, the unwanted ones—we’re going to learn something. We’re going to become more compassionate. We’re going to be able to take our scraps of feeling and compost them into rich soil, filled with empathy and creativity.

I never like seeing any messaging that we should be feeling one way or, because we’re feeling one way, we can’t also be feeling another. All emotions belong in our body, giving us data and valuable information about what’s important to us. For instance, grief is complicated. Upon my father’s death, I believed I should be feeling a certain way, which caused unnecessary suffering and isolation. Learning to embrace and speak honestly about my vast, overlapping, confusing emotional landscape helped me transform my pain and confusion into creative fuel, and also helped me become more curious, accepting, and empathetic to the complicated emotions of others.

“All emotions belong in our body, giving us data and valuable information about what’s important to us.”

3. Community is the antidote to loneliness.

We are in the middle of a loneliness epidemic, exacerbated by social media and the very natural impulses to compare and compete. Especially in a large city where we’re constantly surrounded by people, it can feel extremely isolating, even in non-pandemic times.

I had to create community when I moved to New York. Community-building is a vulnerable, intimate, tender experience, and requires openness and open-mindedness that we’re not often taught. But the reward of community is learning how to grow and heal and self-help with the love of others. Healing isn’t an inside job; it’s not meant to be done alone. We’re relational and social creatures, who literally need each other to survive. Our emotional growth and our movement through wounds and trauma and baggage can be done beautifully in community with others, particularly those who might seem like unlikely friends.

4. You can find magic wherever you are.

I open My Inner Sky with a chapter called “Magical Things I’ve Seen in NY,” which documents moments of delight I’ve witnessed around New York, like a secret handshake between two doormen, or an old lady in a ballgown at a dance club, or the first kiss shared under a streetlamp in the rain.

What’s the secret to finding magic? Paying attention. And what’s the secret to paying attention? I think it has to do with falling a little bit in love with your surroundings. If you think about someone you really love, you probably don’t love the obvious things about them—their megawatt smile, for instance. You fall in love with someone for their flaws, their quirks, their embarrassing little habits, their asymmetry, their imperfections.

“Healing isn’t an inside job; it’s not meant to be done alone.”

The same goes for falling in love with a city. You have to really look around to find the magic—fall a little bit in love with the garbage truck, flirt with the community garden, shimmy a little on the sidewalk. New York is a big, flawed city, but paying close attention will make it feel like a magical small town in a Hallmark holiday movie.

So take a walk, pay attention, and fall in love: magic is bound to come your way.

5. Rituals help us move through our most difficult times.

Humans have rituals for beginnings and endings, but not for the in-between. Not for the complex or for the times we can’t articulate until years later. Even though we invented rituals 200,000 years ago to process our most difficult collective experience, grief, we haven’t come up with many new ones.

We have the science to create babies for the infertile, but we don’t have the vocabulary to hold people when it doesn’t work out. We have the words for estrangement and arguments, but we don’t have cards for those who have lost someone they’re estranged from. We celebrate weddings with bachelorette parties, but we don’t acknowledge the very real grief of losing the life chapter that’s now slipping away. We pretend there are uniform experiences, but each one is as complicated as the human going through it.

When I lost my estranged dad, I didn’t go to his funeral; it didn’t feel like the right way to ritualize a massive loss that wasn’t as straightforward for me as it was for his friends and loved ones. So a few months after he died, I created my own memorial service for him. I invited my closest friends, sang songs he loved, did readings from books he adored, and created a little ceremony that felt very special and specific to my own experience of him as my complicated father.

Naming my experience and moving through it on my own terms helped me reconcile all the contradicting feelings I was going through. We need many more rituals in our society, but they’re not going to magically appear—so we need to create them for ourselves, with each other.

To listen to the audio version read by Mari Andrew, download the Next Big Idea App today: