Steve Wasserman is the publisher of Heyday. He was formerly the deputy editor of the op-ed page and opinion section of the Los Angeles Times, editor of the Los Angeles Times Book Review, editorial director of New Republic Books, publisher and editorial director of Hill and Wang at Farrar, Straus & Giroux and of the Noonday Press, editorial director of Times Books at Random House, and editor at large for Yale University Press. He was also a partner of the literary agency Kneerim & Williams, where he represented authors including Christopher Hitchens, Linda Ronstadt, Robert Scheer, and David Thomson.

What’s the big idea?

Steve Wasserman, the publisher of Heyday and a cultural essayist and social critic of the first rank, tells the story of how his journey through the world of books, ideas, and activism led to an awakening of empathetic sensibility. Through the decades, he has befriended and encountered a number of remarkable people, including Orson Welles, Barbra Streisand, Jackie Kennedy, Susan Sontag, and Christopher Hitchens. In personal reflections on such intellectual crossings, deft maneuvering within the fast-changing publishing industry, and the breadth of his enthusiasms, Wasserman explores the indispensable light of a lively mind.

Below, Steve shares five key insights from his new book, Tell Me Something, Tell Me Anything, Even If It’s a Lie: A Memoir in Essays. Listen to the audio version—read by Steve himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Live all you can: It’s a mistake not to.

The people I most admired and learned from all seemed to share a single attribute: They were hungry for adventure, endlessly curious, and knew that to get smart, it was best to surround themselves with people even smarter than themselves. They were omnivores—about politics, about literature—and knew in their bones that they must always keep an open mind, but not so open that their brains fall out.

When I think of many of the people I’ve been fortunate to meet or work with, I think of their lust for life, their pursuit of aesthetic bliss, their detestation of philistinism, their love of learning, their opposition to ethical and aesthetic shallowness, their insistence on being grown-ups, and their hatred of suffering and death.

2. Stay young by refusing cynicism.

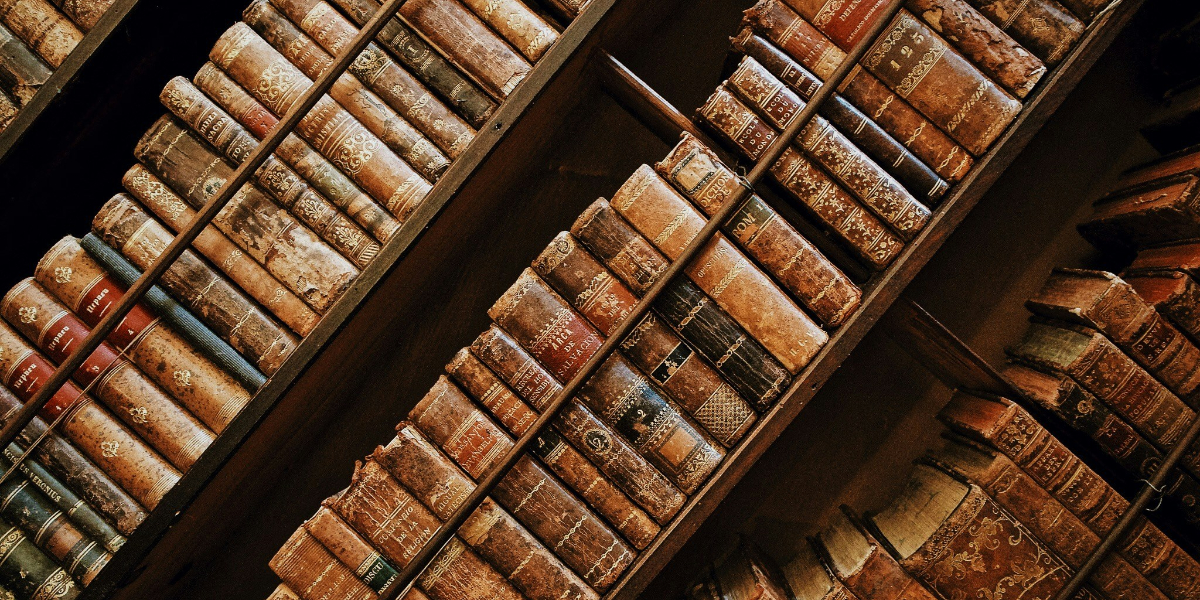

I spent the summer of 1974 living in Susan Sontag’s Manhattan penthouse, Jasper Johns’ former studio. Her walls were lined with her eight thousand books, which she called her “personal retrieval system.” I had just graduated from UC Berkeley and was in New York working with an author who hired me to research the implications of what is now called “globalism,” but which many of us then condemned as “imperialism.”

“Her walls were lined with her eight thousand books, which she called her ‘personal retrieval system.'”

I almost got a crick in my neck from perusing the books in Susan’s apartment, realizing that only now was my real education beginning. For reasons wholly mysterious, I found myself drawn to four blue-backed volumes of The Journals of Andre Gide, the famous French writer. I’d never read him. These, like others in Susan’s library, were filled with her lightly penciled underlinings. I came across a line I never forgot: “I know I shall have entered old age when I awake and no longer find myself filled with outrage at the way things are.”

3. Don’t stay in your lane.

We live in a world that increasingly seeks to throttle ambition, deny imagination, and refuse possibility. Thinking with the blood, remaining hostage to superstition and theocratic models of governance, and championing rigid ideas of identity politics all strike me as denying the essential American dream of self-invention.

I’ve always been a fan of those who sought to burst the bonds of class and rid themselves of the suffocations of race and gender. I agree with the late Christopher Hitchens, who always tried to affirm—and reaffirm—the ideas of secularism, reason, libertarianism, internationalism, and solidarity.

4. Don’t fear difficulty.

When did “difficulty” become suspect in American culture, widely derided as antidemocratic and contemptuously dismissed as evidence of so-called elitism? If a work of art, book, or movie isn’t somehow immediately “understood” or “accessible” by and to large numbers of people, it is often ridiculed as esoteric, obtuse, or even somehow un-American. A culture filled with smooth and familiar consumptions produces rigid mental habits and stultified conceptions in people. Difficulty annoys them, and, having become accustomed to so much pabulum served up by a pandering and invertebrate media, they experience difficulty not just as “difficult” but as an insult.

The exercise of cultural authority and artistic, literary, or aesthetic discrimination is seen as evidence of snobbery, entitlement, and privilege lording it over ordinary folks. A perverse populism increasingly deforms our culture, consigning some works of art to a realm somehow more rarefied and less accessible to a broad public. Thus, choice is constrained, and the tyranny of mass appeal is deepened in the name of democracy.

“A culture filled with smooth and familiar consumptions produces rigid mental habits and stultified conceptions in people.”

The ideal of serious enjoyment of what isn’t instantly understood is rare in American life. It is under constant siege. It is the object of scorn from both left and right. The pleasures of critical thinking ought not to be seen as belonging to the province of an elite. They are the birthright of every citizen. For such pleasures are the very heart of literacy, without which democracy itself is dulled. More than ever, we need a defense of the Eros of difficulty.

5. Cultivate the nobility of contradiction.

Oscar Wilde once said that he distrusted any man whose dictionary did not contain the word “utopia.” As I’ve grown older, I came to believe that he was wrong if, by utopia, he meant a republic where all is ostensibly well, all needs are met, all are happy and content, and all social contradictions are resolved. No such place ever existed, and as long as our species is composed of, as a great philosopher once put it, the broken timber of humanity, it never will.

We should strive to welcome disagreement, dissension, and argument, even fierce intellectual combat, never violent, with confidence that our ideas become sharper and are thrown into clarifying relief when subjected to push-back and counterarguments. Hence my admiration for those critics and crusaders, like Susan Sontag and Christopher Hitchens, among others.

It never mattered whether I agreed with this opinion or that view. What mattered most—and I could feel it in the impress of their sentences and the pitch and roll of their arguments—was that I, like all their lucky readers, was being encouraged to think more rigorously, seriously, and ardently. There seemed in their work no division between intellection and heart. Their example encouraged me to embrace a life of curiosity, irony, debunking, and disputation. Their pleasures were unrivaled.

To listen to the audio version read by author Steve Wasserman, download the Next Big Idea App today: