John Petrocelli is an experimental social psychologist and Professor of Psychology at Wake Forest University. His research examines the causes and consequences of bullshit and bullshitting in order to better understand and improve bullshit detection and disposal. Petrocelli’s research contributions also include attitudes and persuasion and the intersections of counterfactual thinking with learning, memory and decision-making. His research has appeared in the top journals of his field including the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. Petrocelli also serves an Associate Editor of the Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin.

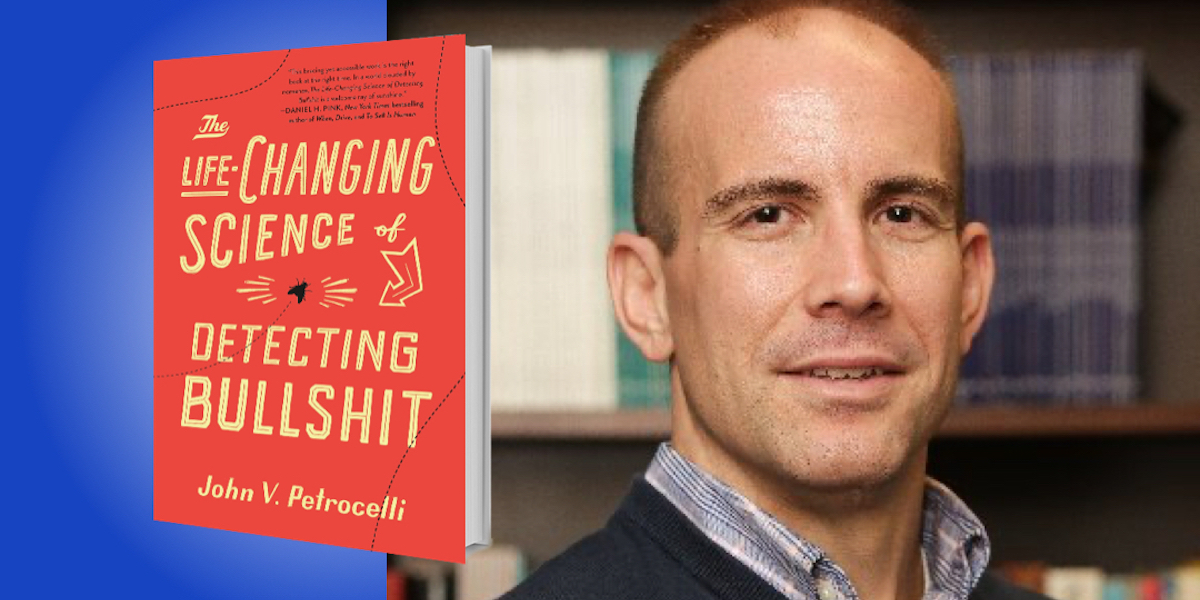

Below, John shares 5 key insights from his new book, The Life-Changing Science of Detecting Bullshit (available now from Amazon). Listen to the audio version—read by John himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Come to grips with the great potential costs of bullshit.

One of the most despised social behaviors is lying. Bullshitting is sometimes confused with lying, but there are critical differences between the two. Liars actually know and care about the truth. A liar’s agenda is to distract us from the truth altogether, and liars also don’t believe what they say. Bullshitters, on the other hand, often do believe what they say, but they don’t know what the truth is; they don’t really care. In fact, sometimes by chance, bullshitters say something correct, but they wouldn’t know it because they aren’t paying any attention to established knowledge, or evidence for their claims. If I said to you that Pluto is a planet, and I know perfectly well that it’s not, then I am lying to you. However, if I said “Pluto is a planet” without any regard for the truth, such that I don’t even know if it’s true or false, then I’m bullshitting you.

Like most people, you probably believe that bullshit is harmless and less insidious than lying. No one is harmed when our uncle claims that in 1982 he was capable of throwing a football over a mountain. Or, if bullshitting children by saying that a special compound in the swimming pool reveals the presence of urine helps prevent such unwanted behaviors, perhaps some bullshit is even beneficial to society.

“Bullshitters often believe what they say, but they don’t know what the truth is; they don’t really care.”

Yet, the notion that bullshit is completely harmless just isn’t so. “I can text while driving without any effects on my performance,” for example, is not only incorrect, but it promotes a flippant attitude toward compelling evidence that suggests otherwise—and a belief in it can cause direct harm to society writ large.

My research suggests that bullshit can also have negative effects on memory, attitudes, opinions, and most importantly, decision-making. Bullshit impacts what we believe to be true, and what we believe to be true is fundamental to human behavior. It’s not only the stuff of unreasonable markups that we often pay for used cars, real estate, wine, jewelry, and so many other things. It’s the stuff of Bernie Madoff’s success in swindling billions of dollars from even the most experienced financial experts with his Ponzi scheme. It’s the stuff underlying the protocols of China’s Great Leap Forward under the direction of Mao Zedong, which resulted in the deaths of 36 million people from starvation. It’s the stuff of Andrew Wakefield’s fraudulent research that has led to the well-debunked assertion that the measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine causes autism in children. And it’s the stuff of senseless conspiracy theories that compel people to storm their own country’s Capitol building in hopes of reversing a fair election. I’m convinced that all of our problems, whether they be personal, interpersonal, professional, or societal are either directly or indirectly linked to mindless bullshit reasoning and communication.

2. Recognize widespread bullibility.

A surprisingly and disturbingly large percentage of really smart people still believe that storing batteries in the freezer will improve their performance, that you can see the Great Wall of China from space, and that diamonds are a sound investment. The major problem with bullshit is that most everyone thinks they can easily detect it, and they therefore feel unaffected by it—despite research clearly demonstrating that bullshit is not easily detected. In fact, research shows that people who are the most confident in their ability to detect bullshit are often the least capable. This is because the mental skills one needs to be competent in something are often the very same mental skills one needs to recognize their own and others’ competence in that domain.

“People who are the most confident in their ability to detect bullshit are often the least capable.”

We’ve come to expect that political leaders and media personalities will bullshit us. Yet most of the bullshit we’re exposed to occurs on an interpersonal level. If we are bullshitted by the evening news, that is one thing—they are paid to have something interesting or provoking to say, even if it is bullshit. But if the people we actually know, care about, and trust are saying the very same thing, it tends to have a stronger influence on our reasoning. When our own attitudes and opinions align, which is quite likely among people we choose to interact with, it is extremely difficult to detect bullshit. These are some of the things that make us naturally bullible.

Bullibility is a blindness to bullshit—an acceptance of a claim as fact by failing to infer from available social cues that the bullshitter has a disregard for the truth or has failed to take reasonable action to find it.

Cues that bullshit is afoot include things like using catchy buzzword salads to describe something, like “Hidden meaning transforms unparalleled abstract beauty.” Does that really mean anything to you? It probably doesn’t. But neither does bandwidth or leverage or win-win in common corporate gibberish, but people often use it. Another cue would be a claim that doesn’t even pass a simple plausibility test. I once heard someone say that the price of a stock decreased by 300%. If something decreased by even 100%, its value is zero. It’s not plausible and it doesn’t make sense.

3. Recognize the signals of bullshit.

Most people are susceptible to the unwanted effects of bullshit because the mental skills that protect them do not come naturally—they must be trained. Part of being a good bullshit detector involves recognizing when, and under what conditions, we will likely encounter it. My own research suggests there are two important factors that impact the production of bullshit.

“The most influential bullshitter is the one staring back at us from the mirror.”

The first is a widespread feeling of obligation to have an opinion about “everything”—but of course, it’s impossible to have a well-informed opinion about everything. Whereas in the past you were expected to have an opinion about big issues, like nuclear energy, war, going to the Moon, or voting rights, now we are expected to have an opinions about these things—but we’re also supposed to have opinions about whether Game of Thrones should add another season, if people should be allowed to carry small dogs in their purses, and if Kim Kardashian should or should not be famous.

The second important factor is that people often generate nonsense when they expect it to be relatively easy to pass bullshit. That is, when people detect cues from the social context suggesting it will be easy to get a “social pass” of acceptance or tolerance for their bullshit. As such, people use bullshit to help them get what they want, gain an advantage, make a positive impression, promote their status, impress others with their knowledge, skills, or competence in something, or help connect with others. We make it easy to get away with bullshit by failing to put up barriers of intolerance. Recognizing the goals of a communicator places us in a better position to detect this unwanted social substance.

4. Ask questions with a healthy attitude of skepticism.

There are lots of classic, tell-tale signs that bullshitters display, including a sole reliance on anecdotal stories, a disregard of any evidence that disconfirms or disqualifies their claims, and the use of senseless and meaningless pseudo-profound language, like “Everyday reality is a dreamscape projected by consciousness.”

However, the reasons people fall for unwanted bullshit have more to do with their untrained critical thinking skills and the important questions they fail to ask, than it has to do with any wizard-like skills of persuasion that bullshit artists might possess. Many psychological studies show that people do not operate as irrationalists, but rather as flawed rationalists. People often operate as if they are prisoners of the confines of their own personal experiences—a terribly problematic method of collecting information. Rather than providing us with clear information that would aid us in “knowing better,” personal experience often leaves us with very messy data that are random, unrepresentative, vague, incomplete, inconsistent, second- or third-hand, and often counter-attitudinal. When we rely on messy data for the development of our most confident beliefs, rather than the fuller picture of truth, we become subject to bullshit.

“Ideas should be treated as ideas, not as facts, unless we obtain compelling evidence.”

Competence in bullshit detection comes from asking important questions to promote critical thinking, such as: What exactly are you saying? How do you know this to be true? What sort of evidence led you to your conclusion? Have you considered any alternatives? All of these questions are designed to diagnose a person’s interest and regard for truth, genuine evidence, and established knowledge. With this diagnosis, and an understanding of the communicator’s credibility, how they believe what they say is true, and what ideas or things they are trying to “sell” us, we can then make an informed decision as to whether or not we “buy” it.

And, because the most influential bullshitter is the one staring back at us from the mirror, we should also ask ourselves: Am I compelled to believe or reject a claim because I really want it to be true or false, or am I compelled by the readily available evidence for or against it?

5. It begins with you.

If we want to do something about the mountains of bullshit we’re exposed to every day, we’ll need to begin transforming our social and communicative culture into one that is committed to truth and values. That will start with a willingness to collectively treat bullshit with as much contempt and disdain as we do lies.

Realizing and accepting that our world is very complex, and understanding that mere explanation is not ipso facto, logic incarnate evidence that a claim or assertion is true, are healthy positions to assume. Ideas should be treated as ideas, not as facts, unless we obtain compelling evidence. Even if most people believe something, that doesn’t make it true. Hundreds of years ago, most everyone believed the Earth was flat. Now we know from multiple, independent lines of inquiry from multiple disciplines that there is compelling reason to conclude that the Earth is shaped much more like a basketball than a hockey puck.

Of course, better information does not always guarantee better judgment and decision-making, but better judgment and decision-making almost always require better information. The decision to be smarter is always an option once we declutter our social environment of useless bullshit.

Even when the forces of conformity are at their strongest, we know from research that it usually only takes one person to stop the unwanted effects of bullshit. We also know that the influence of what people think they should do can outweigh the power of the social norm. Armed with the power of evidence, and perhaps a few allies interested in the same, I believe each of us can play an important role in the struggle against bullshit—and that can be life-changing.

To listen to the audio version read by John Petrocelli, download the Next Big Idea App today: