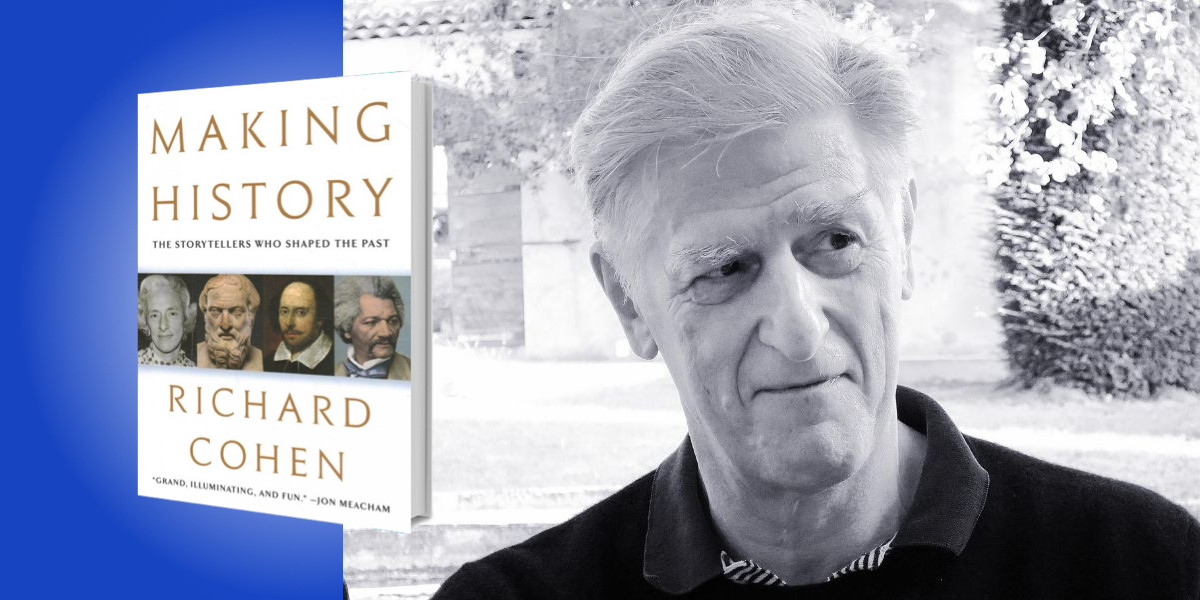

Richard Cohen is the former publishing director of two leading London publishing houses—where he edited such writers as John le Carré, Kingsley Amis, and Madeleine Albright—and author of three previous books: By the Sword, Chasing the Sun, and How to Write Like Tolstoy. A one-time professional fencer, he represented England at three Olympic games.

Below, Richard shares 5 key insights from his new book, Making History: The Storytellers Who Shaped the Past. Listen to the audio version—read by Richard himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. History isn’t new.

The past has always been there, but taking an interest in it hasn’t. Before about 400 B.C., most records were dry chronicles. There’s no evidence of “history” as a concept. The Greeks knew something of their past from oral traditions, but anything that occurred more than three generations distant would be only loosely remembered, if not forgotten altogether. Then along came Herodotus and his book The Histories, and the world changed. Cicero called Herodotus the “Father of History,” but he made so much up—men with eyes in their chests, winged snakes, Egyptians whose semen was black—that Plutarch named him the “Father of Lies.” Yet he brought about a revolution. Although history isn’t a necessary development, certain discoveries are requisite if a civilization is to evolve, and a sense of the past is one of them.

2. History is about historians.

That may seem obvious, but it isn’t. As the novelist Hilary Mantel says, “Beneath every history, there is another history—there is, at least, the life of the historian.” “History” has a double meaning: it’s the past, but also a description of that past. Every author of a work of history is an interpreter, a filter. And they bring with them their prejudices—sometimes the source of their most interesting writing.

“Beneath every history, there is another history—there is, at least, the life of the historian.”

My book looks at people who wrote about the past, from Herodotus on through Livy and Tacitus, Voltaire and Gibbon, von Ranke and Machiavelli, Ulysses S. Grant and Winston Churchill, all the way up to the television age. And it’s not dry historiography, but about the demands of patronage, the need to make a living, physical disabilities, changing fashions, religious beliefs, patriotic sensibilities, love affairs (Voltaire’s mistress stole his first work of history, because it interfered with their love life), the longing for fame, cultural pressures, and the rivalries of scholars. Oh, those rivalries! When in 1979 the British historian Hugh Trevor-Roper was offered a peerage, he thought of refusing the honor, but his wife told him, “Think of the people it will infuriate.” That settled the matter.

All these historians had their own slant, their own agendas, even when they didn’t think they did. In Tom Stoppard’s Night and Day, a journalist says of his paper, “It’s not on any side. It’s an objective fact-gathering organization.” And a colleague asks: “Yes, but is it objective-for or objective-against?”

I asked the historian Eric Hobsbawm whether it was possible to be objective, and he just laughed. “Of course not,” he said. “But I try to obey the rules.”

3. History is too important to be left to professional historians.

In a sense, everyone is a historian. We say to a friend, “Yesterday, I was walking along the street and bumped into Lady Gaga”—or whatever. We select an incident, shape it, and tell it.

“I asked the historian Eric Hobsbawm whether it was possible to be objective, and he just laughed.”

The touchstone for my book was who has influenced our understanding of the past. So I’ve included the writers of the Bible, journalists with their “first drafts of history,” historical novelists, from Sir Walter Scott to Hilary Mantel. A diarist, Samuel Pepys, whose recording of the Great Fire of London in 1666 may be a valuable source, and was also history written on the spot, as it was happening. As for Shakespeare, over half of his plays are histories. He was a propagandist, pushing the Tudor cause, but he gives us a more lasting impression of the Plantagenet kings and queens than any other source—the fecklessness of Richard II, the exuberance of Henry V, the villainy of Richard III. Our sense of all those figures are largely Shakespeare’s. Dramatists, for good or ill, are historians, too.

4. Women have a hard time of it from historians—and as historians.

Until the last hundred years, women hardly get a look in. In The Odyssey, Telemachus informs his mother, Penelope, that “speech will be the business of men,” and so it has been through the centuries. Aristotle saw women as defective men, and a 1486 work commissioned by the Papacy branded woman as “an imperfect animal, a necessary evil.” If they dared write good history—or good anything—it was dismissed. A 17th-century New England poetess wrote: “If what I do prove well, it won’t advance, / They’ll say it’s stolen, or else it was by chance.” Or, jumping forward in time, the 1985 Pulitzer Prize winner Carolyn Kizer: “We are the custodians of the world’s best-kept secret: Merely the private lives of one-half of humanity.”

Women’s history wasn’t written about, and women weren’t allowed to write their own accounts. Now the world has changed. Barbara Tuchman, Doris Kearns Godwin, and Mary Beard are bestselling authors. Even so, if you’re researching a woman from the past, it can be a thankless task. Her diaries, letters, and private ruminations will often have been destroyed—or filed away under the name of her husband.

“History has the obligation to tell the truth to power. We need to protect it.”

5. History is in crisis.

It’s not just that so much writing about the past comes to us as myth or propaganda. It’s that, right now, dictators around the world are trying to distort the historical record.

Last November, President Xi of China announced that he intended to reshape his country’s history. President Putin, even before the war in Ukraine and the constant false commentary coming from the Kremlin, has been dead set on making textbooks in Russia conform to the history he thinks people should learn. “All sorts of things happen in the history of every state,” he told a conference of teachers in 2007. “And we cannot allow ourselves to be saddled with guilt.” Four days later, he introduced a law saying that his government would decide which textbooks should be used in Russian schools. Heard of the cartoon of a king on his throne turning to a courtier? “I’m concerned about my legacy,” he says. “Kill all the historians.”

In the United States, the country is split about what version of its history should be taught. Critical Race Theory, “white” history, the 1619 Project, ex-President Trump’s 1776 Commission—to date, 14 states in the U.S. have banned Critical Race Theory. So what version of the past should we agree on? The arguments are made worse by the prevalence of “false facts,” the lack of control—whatever such control should be—of Facebook and Twitter and Instagram, and the internet generally.

Thus the most important of my five big ideas: we must be on our watch. History has the obligation to tell the truth to power. We need to protect it.

To listen to the audio version read by author Richard Cohen, download the Next Big Idea App today: