Dr. Jenni Nuttall is a professor of Medieval English Literature and Language at Exeter College at the University of Oxford. She was awarded a teaching excellence award by the University of Oxford. She has a Doctorate of Philosophy from Oxford and completed the University of East Anglia’s MA in creative writing.

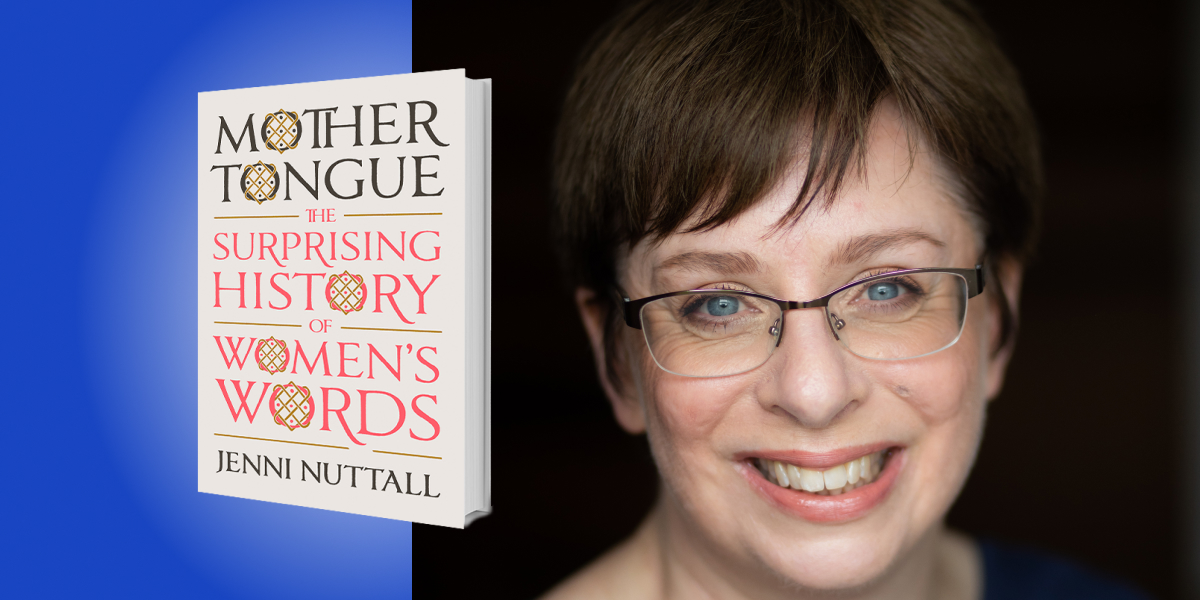

Below, Jenni shares 5 key insights from her new book, Mother Tongue: The Surprising History of Women’s Words. Listen to the audio version—read by Jenni herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. The past wasn’t silent about women’s lives and experiences.

As you might expect, there’s plenty of sexism and misogyny in the language of the past, but there are also evocative records of women and their lives. There is much vocabulary related to women’s bodies, lives, and experiences in the first thousand years of the English language. English developed from an immigrant language brought to the British Isles in the fifth and sixth centuries, to a language exported around the world by colonization and exploration.

There are 12th-century descriptions of what it’s like to live with the fear of an abusive partner and of the hard work of caring for a small baby. Medieval lyrics have also described the fear felt by a young woman who is being pestered by a persistent stranger, what we would call street harassment today. Eighteenth-century poems describe the challenges of working women who are juggling childcare and wage-earning; words like these can resonate powerfully with us today.

2. Newer isn’t necessarily better when it comes to words.

Many of our current words for female sexual and reproductive body parts and processes are either formal or euphemistic. You might think of words like menstruation, or names like uterus or vulva. Some of them come into English from Greek and Latin and are the products of scientific discovery and medical terminology. We might feel uncomfortable using words like this, not only because these body parts and their names are often taboo (that is, considered to be avoided or danced around in public discourse), but also because the words themselves can feel difficult and confusing. Surveys suggest that many of us can’t accurately match all of the technical terms with the right body parts on a diagram.

However, before these words became the usual names, English had some other alternatives. Being on your period was called being on your flowers: it was understood that just as flowers precede fruits, regular menstruation was helpful for fertility. Before we used abstract Latinate words for female sexual anatomy, there were vernacular alternatives like “the mother,” meaning the womb, “womb-gate” or “wicket” for the vulva (a wicket is an old name for a small gate) and “lips,” “wings” or “nymphs” for what we now call the labia.

“Before we used abstract Latinate words for female sexual anatomy, there were vernacular alternatives.”

One Renaissance physician, Thomas Raynalde, wrote a book in the mid-sixteenth century telling women what to expect during pregnancy and labor. He calls the vulva the “passage port,” the vagina the “womb passage,” and the cervix the “womb port.” A port is a gateway, like those stone archways that give you entrance to a walled city. We can’t turn the clock back and parachute these older words into our contemporary English, but these alternative names might inspire us to speak as eloquently as we can about female anatomy.

3. The backstories of our words matter.

You don’t need to know a word’s etymology to use it as part of today’s English, but finding out about a word’s backstory reveals some of the assumptions and biases which we’ve inherited from the past. Take the words which we use to say that someone is growing another human being inside them. We have words and phrases like being or falling pregnant, expecting, or carrying a child. They all sound rather passive, as if the mother-to-be isn’t doing much more than transporting her fetus around or simply waiting patiently for a baby to be delivered. Gestation, a more formal term, sounds more impressive, but that term too comes from a Latin verb which simply means “to carry.” These words minimize pregnancy, seeing the female body as a mostly passive carrier rather than an active creator.

Other words, which English once had but which are now lost, give us a different way of thinking about pregnancy. In medieval English a woman could be “childing,” making and birthing a child, or “greating,” growing greater or bigger or “barnishing,” from barn, like Scottish bairn, meaning a child, so literally child-making. These older verbs get closer to a more active meaning, one which 20th century feminists reclaimed with concepts like “reproductive labor,” the work (done predominantly by women) which creates and nurtures new generations of humans.

4. Old words can remind us of hidden histories.

The English of the past records a history of women earning money for themselves and their households. In medieval London there were “throwsters” who twisted silk filaments into thread and yarn, and “silkwomen” who made ribbons, laces, hairnets and other kinds of trims with this silk thread. This was big business, rather than a mere cottage industry: in the 15th century, the “silkwomen” told parliament that they had trained over a thousand girls as apprentices.

Most women in the past were generally excluded from higher-paying trades and professions. They worked at the margins of the economy, usually for lower pay than men doing equivalent work. Some women’s work was even physically very strenuous, like the “mayds in the craine” who turned a treadmill which powered a crane lifting stone blocks in Cheshire in the 1560s.

“A drudge was a word for a female servant, one expected to do menial jobs in a household.”

Older words can also tell a kind of truth about women’s work in the past. A drudge was a word for a female servant, one expected to do menial jobs in a household. That gives us our modern word drudgery, the often boring work needed to keep everyday life going. The origins of the term spinster, meaning a single woman, are also revealing. A spinster was originally a woman who spun wool with a spindle or a wheel. This was often low paid work, but not exclusively done by unmarried women. That particular association led to spinster becoming a word for a woman who had not yet married.

5. History is never simple and always surprising.

Things that we take for granted often turn out to be the result of changing fashions and customs. Many women dislike having to choose between the title of Mrs. or Miss based on their marital status. The modern title Ms. tries to solve this problem, but that choice between Miss or Mrs. only took this form in the 1740s, when unmarried adult women, following a French fashion, began to be called Miss. Before that point in time, any woman of sufficient social status was called Mrs. whether she was married or unmarried. Miss was kept as a polite term of address for female children. The new fashion for adult Miss allowed marriageable daughters in wealthier families to be distinguished from servants and tradeswomen who, if they had a certain degree of seniority, were called Mrs. whether they were married or not.

Take a familiar-feeling word like girl: when it arrived in English around the year 1300, it referred to both male and female children. It was used for female children only, in opposition to the word boy, at the start of the sixteenth century. Then for the next 150 years or so, this new concept, “girl,” was often used very pointedly to refer to female children and young women who are in some way rebellious or unconventional. According to the customs of the time, a “girl” would be those who are stepping outside the categories of maid or daughter. Girls were already rebel girls in the 16th century. Even the most everyday words have surprising past lives.

To listen to the audio version read by author Jenni Nuttall, download the Next Big Idea App today: