Carl R. Trueman, PhD is professor of biblical and religious studies at Grove City College. He is an esteemed church historian and previously served as the William E. Simon Fellow in Religion and Public Life at Princeton University.

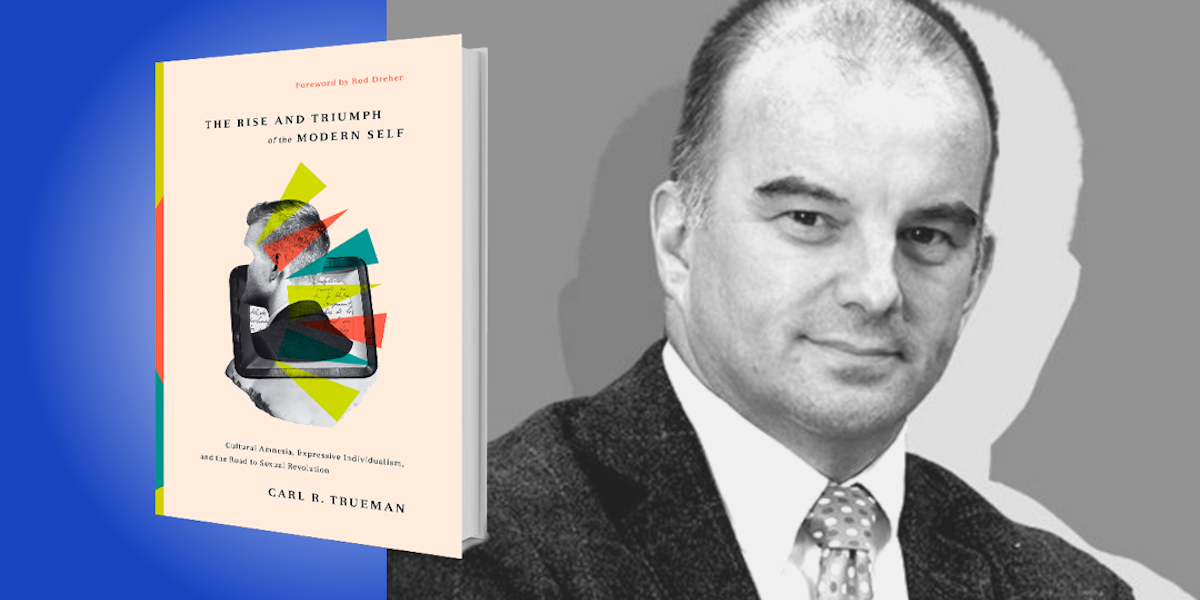

Below, Carl shares 5 key insights from his new book, The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self: Cultural Amnesia, Expressive Individualism, and the Road to Sexual Revolution. Download the Next Big Idea App to enjoy more audio “Book Bites,” plus Ideas of the Day, ad-free podcast episodes, and more.

1. The times, they are a-changin’.

2020 has witnessed a time of great chaos in American society, as divisive political rhetoric has been matched by violence in the streets. Everyone seems thin-skinned, willing to take offense at the smallest perceived slight or disagreement. And things that have traditionally been regarded as virtues—like freedom of speech and freedom of religion—are now being challenged as not being good for society at all, but rather as providing cover for hatred and bigotry. But the apparent chaos of our cultural moment has been a long time in the making—and it all has to do with a fundamental redefinition of the self.

2. I can’t get no satisfaction—at least, not as my grandfather got it.

My grandfather was a sheet metal worker in a factory from age 14 to 65. It was hard, monotonous work, the kind that I would have hated. Now, if he were still alive and I asked him if he got satisfaction from his work, I suspect he would reply, “Of course. I received an honest day’s pay for an honest day’s work, and I was therefore able to house, clothe, and feed my family.” For my grandfather, the primary purpose, the primary satisfaction of work was not feeling good inside—it was providing for others. But for me, the satisfaction I get from my job is inwardly directed. I love teaching because it is intrinsically enjoyable for me, personally. This shift in what constitutes satisfaction or happiness is central to today’s most contentious issues, from sexual identity to race.

“It does me no injury for my neighbor to say that there are 20 gods or no God. It neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg.”

3. Oppression ain’t what it used to be.

Once the self, our understanding of who we are and what we are for, becomes focused on an inner sense of well-being, everything changes—especially how we think of oppression. To my grandfather, oppression was the opposite of what gave him satisfaction, like not being paid an honest day’s wage for an honest day’s work, or perhaps not being able to find paid employment at all. Oppression was external, economic, and objectively quantifiable. Today, however, oppression is often defined in terms of things such as hate speech, or the refusal of somebody to recognize the identity of some other personal group. In short, it is something that disrupts, hinders, or even prevents someone’s inner feelings of happiness.

This has dramatic implications for public life and for politics. Thomas Jefferson once famously quipped, “It does me no injury for my neighbor to say that there are 20 gods or no God. It neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg.” He lived in a world where flourishing and oppression were understood primarily in economic terms, but today, the most important things in life are feelings. Whether my pocket gets picked or my leg broken may still be an issue, but now we add getting my feelings hurt to the mix. As such, the notions of oppression and what is “dangerous” have been massively expanded.

4. Words are now weapons.

A Hollywood actor recently came out as a transgender male. He asked to be called by the new name “Elliot Page,” and to be referred to with appropriate male pronouns. This raised an interesting public discussion about the issue of “deadnaming,” or using pre-transitional names and pronouns when referring to a present day, transgender person. Yet deadnaming does not, to use Jefferson’s phrase, either pick someone’s pocket or break their leg—so why is it deemed so offensive in modern society?

“People have become defined by what they sexually desire, so sex changed from a private activity to a public identity.”

Many of us still remember our response to playground taunts when we were young. We would chant, “Sticks and stones may break my bones, but words will never hurt me.” But words really do hurt—they always have. And even more so now, in a world where one’s feelings are central to their sense of self. Indeed, we might say that words are now weapons, weapons that can shatter someone else’s psychological peace and happiness, which is placed at the heart of the modern moral universe. In Jefferson’s day, freedoms of speech and religion guaranteed a free and safe society, but in today’s world, they will increasingly come to be seen to do the opposite, as they are seen to give cover for people to use words that seemingly do harm to others.

5. Our private lives are now public property.

The sexual revolution did not simply overturn old taboos and restrictions about sexual behavior, as people have always broken whatever sexual rules were in place. The sexual revolution was more radical—it made sexual desire definitive of who we are as human beings. 200 years ago, if you had asked somebody if they were straight or gay or bisexual, they would have thought you were from another planet. Yet today, these categories are basic elements of our cultural vocabulary. People have become defined by what they sexually desire, so sex changed from a private activity to a public identity. Now it’s not so much about morality and behavior, but about self-worth. That’s why the battles over things such as gay marriage and transgender rights go to the very heart of what it means to be human.

For more Book Bites, download the Next Big Idea App today: