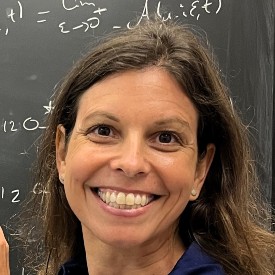

Nick Romeo is a journalist on policy and ideas for The New Yorker and teaches at the Graduate School of Journalism at the University of California. He has also written for the New York Times, The Washington Post, National Geographic, Rolling Stone, The Atlantic, The MIT Technology Review, and many other publications.

Below, Nick shares five key insights from his new book, The Alternative: How to Build a Just Economy. Listen to the audio version—read by Nick himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Externalities enable dangerous magical thinking.

If you buy an inexpensive chocolate bar or hamburger, you might look at the price and feel like you’re getting a good deal. But what if your chocolate is made from cocoa grown by forced child workers in North Africa, or your hamburger comes from a cow raised and fed by destroying biodiversity in the Amazon?

What economists call the externalities of these goods—costs not included in the price—cause great human suffering and environmental collapse. The cheap price for the consumer is an illusion. Ignoring externalities does not make them disappear. It just makes someone else pay them.

Imagine a world in which the most relevant externalities for any good were immediately visible. Most people don’t want to buy goods and services that destroy the natural world and harm other humans. Yet nearly all of us, especially in wealthy countries, do this. If we knew the true externalities of what we consume, we would likely make different choices that would motivate businesses to decrease these externalities and compel policymakers to do the same. True cost accounting methods and the true price movement, popular in the Netherlands, are supplying this crucial information to consumers and policy-makers alike.

2. Worker ownership can build a strong middle class.

In America, probably the most popular form of worker ownership is called the ESOP, or employee stock ownership plan. If you work for a company with an ESOP, you accumulate ownership shares over time and redeem these upon retiring or leaving the company. Paying workers higher wages is great, but low-wage workers are unlikely to accumulate real wealth through wage increases alone.

ESOPs are different. A recent study found that median retirement savings for low-to-moderate-income workers at ESOPs in 16 states were $215,000. In comparison, median retirement savings for the average worker nationally were just $17,000.

“What if the 100 largest companies in America instituted profit-sharing or worker ownership plans?”

Profit sharing and employee ownership plans help build these large chunks of capital, catapulting working people into the middle class. Profit-sharing plans can also exist at publicly traded companies. If Amazon’s employees in 2018 had owned as much of their employer’s stock as Sears department store employees did in the 1950s, each Amazon worker would have owned shares worth $381,000. What if the 100 largest companies in America instituted profit-sharing or worker ownership plans? This country would have a much larger middle class.

3. We can make gig work less exploitative.

To reform the gig economy, we must find a strategy that can retain its positive aspects while eliminating the negative ones. One positive is that people like and sometimes need jobs with flexible hours. If current trends continue, 86 million Americans will be working as freelancers by 2027—that’s more than 50 percent of the workforce. But the negatives of gig work are considerable: people don’t like low wages, no sick leave or other benefits, an algorithm as a boss, constantly changing hours and rules, and few prospects for advancement.

One compelling alternative is to create markets for flexible work that operate as public utilities. Just as public utilities already supply water, electricity, and road networks in many areas, they could also provide the digital infrastructure for flexible labor markets. Instead of relying entirely on a private platform owned by a single company for work, job seekers could see many different jobs offered by many employers on one platform. Private gig-work companies often take a transaction fee of 30 percent or more. A public option could charge a much smaller figure— between two and five percent. This would make such a platform cheaper for consumers and would drive better wages for workers. Enforcement of labor laws and benefits for workers could be easily monitored.

The system could also respond to workers’ goals and preferences by connecting them with opportunities and job training. In short, the platform’s design could be engineered to promote the public interest, not to make venture capitalists money. This model is already being tried in a handful of cities around America, and it’s generating strong interest from regional and national governments around the world.

4. Job Guarantees have enormous psychological and economic benefits.

The 1946 Universal Declaration of Human Rights established “the right to.. protection against unemployment.” A recent analysis of data from 63 countries attributed one in five suicides to unemployment, which is also implicated in addiction, depression, and many other ailments. This doesn’t mean that any job is better than no job, but it does suggest that even with a universal basic income, many people would still want to work.

In a fascinating Job Guarantee experiment currently being piloted in Austria, each of the 100-plus participants had the option to keep receiving unemployment benefits. Yet all chose to join the Job Guarantee .“I was psychologically destroyed,” one man told me, recalling a long period of unemployment before he joined the study. Now, he and many other participants have experienced significant improvements in their mental health. The program costs no more than what the state already spends on its unemployment program.

“Even with a universal basic income, many people would still want to work.”

It also has other advantages. First, Job Guarantees mobilize a latent workforce to meet urgent local needs, from care work to the green transition. Second, Job Guarantees can have broad positive impacts on labor markets: With a better outside option, many people would abandon jobs that are dangerous, poorly paid, tedious, or unsatisfying. Would some low-quality employers struggle to attract workers? Probably so. But for supporters of job guarantees, this is the point.

5. City governments can bypass national political dysfunction, combating climate change and strengthening democracy.

There are two new, innovative models for city budgets. The first is climate budgeting, in which Oslo, the capital of Norway, is a global leader. Each year, every department in the city identifies specific policies and actions to reduce its emissions. It could be anything from using electric vehicles on big construction sites to phasing out meat in school lunches. Oslo’s climate budget isn’t just one line item among others. It’s a way for cities to measure how much different policies can reduce emissions and to shape their decisions accordingly. Recent modeling for Oslo predicts a decline in greenhouse gas emissions of 72 percent by 2030.

The second model is called participatory budgeting. It gives citizens direct democratic control over a significant proportion of a city’s budget. Every year, tens of thousands of people in the Portuguese city of Cascais vote on projects proposed by their fellow citizens. Winning projects receive millions of euros and are swiftly implemented. Many projects tackle essential infrastructural needs: improvements to schools, roads, old buildings, green spaces, and athletic facilities are frequent winners.

This model has implications beyond Portugal; even when federal spending is limited and national politics dysfunctional, participatory budgeting directly engages citizens in politics. From 2011 to 2021, almost half a million people in Cascais have allocated €45 million to 198 winning projects. “Participatory democracy and collaborative democracy are great ways of avoiding extremisms,” the mayor of Cascais told me.

To listen to the audio version read by author Nick Romeo, download the Next Big Idea App today: