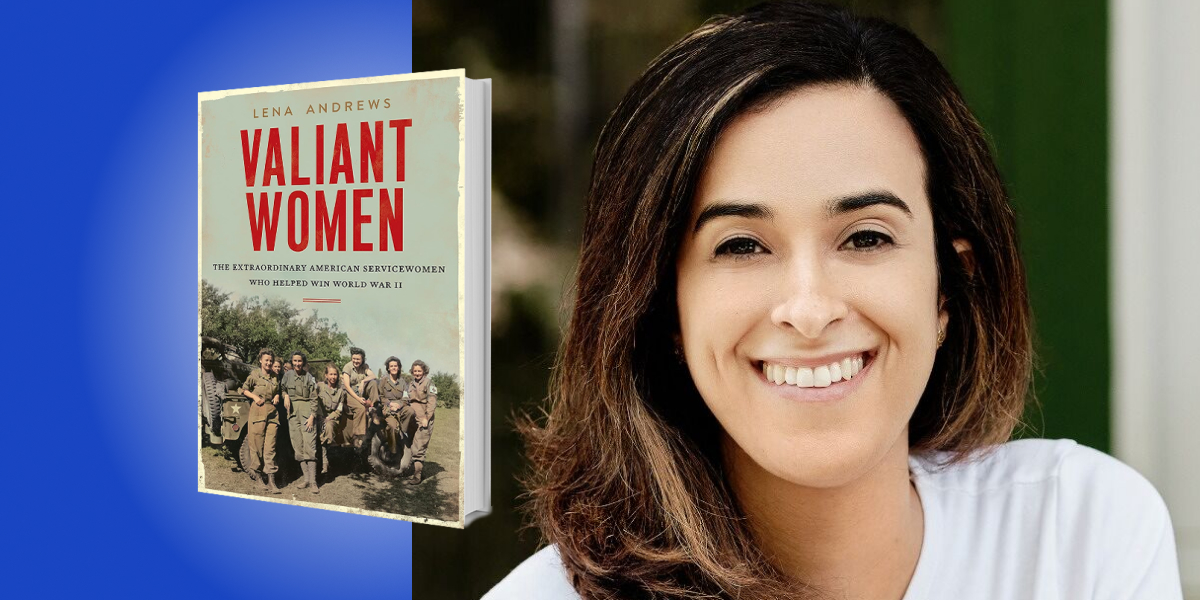

Lena Andrews is a military analyst at the Central Intelligence Agency. She received her Ph.D. in political science from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, specializing in international relations and security studies. She has spent more than a decade in foreign policy, having previously worked at the RAND Corporation and the United States Institute of Peace.

Below, Lena shares 5 key insights from her new book, Valiant Women: The Extraordinary American Servicewomen Who Helped Win World War II. Listen to the audio version—read by Lena herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. No one succeeds alone.

Most human endeavors are team sports—and nowhere is this more the case than in war. Unfortunately, this observation tends to be missing from most popular depictions of conflict, leaving many people to assume that warfighting begins and ends on the frontline.

This could not be further from the truth, and there is no better example of this than World War II. Despite spending decades telling the story of World War II, our existing understanding of the Allied strategy fails to acknowledge, let alone appreciate, the contribution of the support forces that formed the backbone of battlefield operations and helped win the war. The underappreciation of these units is disappointing not only because it results in an incomplete understanding of the war, but also because support units are often where we find the contributions of American servicewomen during World War II.

This included women like Ann Baumgartner, who test-flew the Army Air Force’s most advanced planes to determine if they were mission-ready, including the B-29 Superfortress, which dropped the bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. This also includes Susan Ahn, who was one of the Navy women tasked with training sailors to use machine guns and fly planes in Pacific combat.

From test pilots to gunnery instructors to tank mechanics to translators to pigeon trainers, women just like Baumgartner and Ahn ensured that frontline forces got the support they needed, exactly when and where they needed it. In these and, literally, hundreds of other military occupations, servicewomen were doing tasks that served as the foundation for Allied victory. All these individual contributions added up to a whole that allowed us to win the war. It’s time we recognize their impact.

2. History remembers integrity.

The stark reality of the time is that many of the American servicewomen performing these essential tasks simultaneously faced appalling instances of mistreatment, including discrimination, harassment, and violent attacks by men in and out of uniform. In many cases, this mistreatment was most shocking when it was directed at servicewomen of color, and it stood in stark contrast to the integrity with which these women responded.

There is no better example of this integrity than Charity Adams, who led the largest unit of Black Army women in Europe, the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion. After arriving overseas, the Six Triple Eight soon proved indispensable: they cleared a six-month backlog of mail in a matter of weeks, ensuring troops got an essential morale boost by getting word from their loved ones. They were so effective that they could sort over 60,000 pieces of mail in a single shift, far exceeding the standard of their predecessors.

“Her response to mistreatment was always characterized by extraordinary poise and dignity.”

Adams and her unit often found themselves on the receiving end of racist and sexist attacks in the field. But, without fail, Adams responded to these instances of discrimination and mistreatment with extraordinary integrity. For instance, when it was suggested that her unit stay in a segregated hotel while in London, Adams simply refused to stay there. On another occasion, when the Red Cross told Adams that it insisted on setting up a segregated recreation facility for the Six Triple Eight, she declined to accept the equipment, saying, “If our girls are not good enough to visit their club, then their equipment is not good enough for us to use.” Her response to mistreatment was always characterized by extraordinary poise and dignity.

In the end, Adams’ integrity won the day: history does not remember the individuals who spewed racist and sexist vitriol at the Six Triple Eight, but we do remember Adams. When she left the Women’s Army Corps, she was one of the most senior-ranking women in the service, Black or white, and her unit, the Six Triple Eight, received the Congressional Gold Medal for exemplary service.

3. Necessity is the mother of invention.

The director of the Navy women’s program, Mildred McAfee, often liked to tell a story about the women under her command. This group of women, cleverly called the Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES,) overcame the unfriendly impediments that men sometimes threw in their way.

As McAfee tells it, two WAVES were sent to a base to replace two male sailors. The men, however, were not eager to trade their positions working in a stateside warehouse for Pacific combat. To prove their indispensability and avoid their fate, the men greeted the women with an impossible task on their first day: moving a set of truck tires up to the top storage shelf. Knowing the women did not have the strength to lift the tires, the men simply wished them luck and went to get lunch. When they returned to check on the women, they found, much to their surprise, all of the tires in their spot high above the warehouse floor. “How on earth did you do it?” they asked, incredulously. The women responded, simply, “We rigged a pulley, of course.”

Women in uniform were creative because they had to be, and it usually worked.

4. The proof is in the pudding.

Most American World War II commanders could not—at first—see the value of women serving in uniform. It was only after much prodding, and some arm-twisting, that senior officers like George Marshall, Dwight Eisenhower, and Hap Arnold were willing to consider women as a solution to the massive manpower challenges they were facing. Eisenhower, for instance, admitted after the war that he got the question of integrating women wrong at the start of the war. “When this project was proposed in the beginning of the war, like most old soldiers, I was violently against it,” he remembered, adding, “I thought a tremendous number of difficulties would occur.” But, in the end, he admitted, “None of that occurred.”

“Eisenhower had watched firsthand as the women under his command took on extraordinary risks to perform their essential duties.”

Eisenhower, like most men in the armed forces, attributed his conversion on the issue of women to exposure. He had seen their effectiveness in operations he commanded from the very beginning of the war when he first requested a detachment of women to help his headquarters keep pace with the overwhelming amount of paper flowing through it at the start of the North Africa invasion. Eisenhower instantly recognized the bravery and effectiveness of these women, which was hard to deny: the women who were first deployed to Eisenhower’s headquarters were on a British ship that was torpedoed just before it arrived in the harbor. They were forced to evacuate onto a small landing craft, where they spent hours collecting men from the water. They were forced to direct the life raft themselves because most of the men aboard were too seasick to be useful. Eventually, they were greeted on shore by one of the most senior-ranking U.S. military officials in the theater with a bundle of oranges.

In this, and many other instances, Eisenhower had watched firsthand as the women under his command took on extraordinary risks to perform their essential duties. In the end, it was the demonstrated proficiency of women that converted men in uniform—from senior commanders down through the ranks—to support the integration of servicewomen. It was women’s skills, not their gender, that made all the difference.

5. We must know our story—and that means all of it.

At the end of the war, President Harry Truman urged Americans to remember the veterans of World War II, saying, “Our debt to the heroic men and valiant women in the service of our country can never be repaid. They have earned our undying gratitude. America will never forget their sacrifices.” While we have, rightly, done a good job of honoring the heroic men who served in World War II, we still have a great deal of work to do in remembering the valiant women who answered the same call, donned the same uniform, and helped win World War II.

Women veterans are as deserving of our attention and admiration as anyone else. If you have the privilege of knowing a woman veteran, take a moment to ask her about her service and listen carefully to what she tells you. You will not regret it—and you may even find yourself writing a book about it.

To listen to the audio version read by author Lena Andrews, download the Next Big Idea App today: